When the last light of October fades and the moon ascends over rustling trees, the world prepares for a night unlike any other – a night when imagination takes flight, when shadows whisper stories of the ancient past, and when the living playfully dance with the idea of the unseen.

That night is Halloween, celebrated every year on October 31, a festival that fuses ancient Celtic mysticism, Christian traditions, and modern revelry into a spectacular symphony of the eerie and the joyous.

From Samhain to Halloween:

The Ancient Origins

Long before Halloween became a costume-clad celebration, it began as Samhain, an ancient Celtic festival marking the end of the harvest and the beginning of the dark, cold months. Over 2,000 years ago, the Celts of Ireland, Scotland, and northern France viewed this period as a sacred turning point – the boundary between life and death grew porous, and spirits roamed freely among the living.

People lit massive bonfires to honor their gods, and Druids, the Celtic priests, performed divination rituals to foresee the coming winter. Villagers wore masks and animal hides to disguise themselves from wandering spirits and carried embers from the sacred fires back home to relight their hearths for protection and prosperity.

Samhain was a night of both awe and fear – a time to celebrate the harvest’s bounty but also to prepare for nature’s dormancy. It was not morbid, but mystical – a recognition that life and death are part of the same cosmic rhythm.

Christianization: From All Hallows’ Eve to Halloween

As Christianity spread through Europe, many pagan festivals were reinterpreted through a Christian lens. In the 8th century, Pope Gregory III declared November 1 as All Saints’ Day (All Hallows’ Day), a time to honor saints and martyrs. The night before – All Hallows’ Eve – retained many of the older customs and superstitions.

Eventually, “All Hallows’ Eve” contracted into “Halloween.” The spiritual idea persisted: souls of the departed could revisit their homes, and prayers, offerings, and vigil lights were used to guide or comfort them. In England, people offered “soul cakes” to the poor in exchange for prayers for the dead – a practice that later evolved into the modern trick-or-treating tradition.

The Journey to the New World

When Irish and Scottish immigrants arrived in America during the 19th century, they brought their Halloween customs with them. In the New World, the festival gradually transformed from a mystical ritual into a communal celebration.

By the early 20th century, Halloween had become a lively event with parades, costume parties, ghost stories, and trick-or-treating. Children went door-to-door in disguise, echoing the Celtic belief in masking one’s identity to blend with spirits.

It was also in America that the pumpkin became Halloween’s most iconic symbol. The Irish tale of “Stingy Jack”, who roamed the Earth with a lantern carved from a turnip, found new expression in the readily available pumpkin – larger, brighter, and perfect for carving. Thus was born the jack-o’-lantern, whose flickering face became the glowing heart of Halloween.

Symbols of the Season:

Meaning Behind the Magic

Every image associated with Halloween carries deep symbolism:

– The Jack-o’-Lantern represents both protection and mischief – a beacon to guide lost souls and award against evil.

– Witches and Broomsticks symbolize the power of transformation – women once revered as healers and midwives, later feared as agents of dark magic.

– Black Cats, Bats, and Owls were thought to accompany witches, bridging the world between the living and the supernatural.

– Skeletons and Skulls remind us that death is not an end, but part of an eternal cycle.

– Orange and Black – the festival’s signature colors – reflect harvest (orange) and darkness (black), life and death intertwined.

Even the seemingly playful trick-or-treat ritual holds echoes of ancient spiritual reciprocity: giving and receiving blessings, sharing abundance, and honoring unseen forces.

Halloween Around the World

Though Halloween is most popular in North America, its spirit is global. Across cultures, October and early November mark a time to remember the dead and celebrate life’s continuity.

– Ireland & Scotland: Bonfires, torchlight parades, and storytelling keep the spirit of Samhain alive. In Derry, Northern Ireland, Europe’s largest Halloween carnival merges ancient and modern imagery.

– Mexico: Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead), held from October 31 to November 2, transforms remembrance into an art form. Families build colorful ofrendas (altars) with marigolds, sugar skulls, and food offerings, inviting ancestors to join in celebration.

– The Philippines: In Pangangaluluwa, people sing the souls of the departed, similar to the medieval European soul cake tradition.

– Japan: Halloween has become a festival of fashion and fun, especially in Tokyo’s Shibuya district, where thousands parade in elaborate costumes.

– Italy and Spain: Families visit cemeteries, light candles, and share food in memory of loved ones, blending Catholic and folk customs.

– India: Though Halloween is relatively new, it is growing in urban centers as a creative cultural event – costume parties, pumpkin décor, and themed gatherings often coincide with Diwali festivities, offering a colorful contrast of light and shadow.

The Psychology of Halloween

Why does humanity continue to celebrate a night devoted to ghosts, darkness, and the unknown?

Psychologists suggest that Halloween offers a safe confrontation with fear. It allows both children and adults to explore their darker emotions – curiosity about death, fascination with the supernatural – in a controlled, joyful environment.

By donning masks, people symbolically shed their everyday identities. The costume, in many ways, becomes a form of liberation – an opportunity to express hidden parts of the self, to laugh at fear, and to embrace the mystery of existence.

As cultural historian Lesley Pratt Bannatyne wrote, “Halloween is the day we let our imaginations rule, and we make peace with the darkness.”

Eco-Friendly Halloween

In recent years, a green Halloween movement has emerged. Conscious revelers are turning toward sustainable costumes, natural decorations, and pumpkin composting to minimize waste. Homemade treats and thrift-store finds are replacing disposable plastics, echoing the original harvest festival’s connection to the earth and cycles of renewal.

Many communities now organize pumpkin walks, harvest fairs, and charity trick-or-treats, reviving Halloween’s social spirit while caring for the planet.

Halloween, at its essence, is far more than an evening of spooks and sweets. It is a reminder that darkness and light coexist – that fear, death, and mystery are not enemies of life but companions on the same journey.

From the ancient fires of Samhain to the glowing pumpkins of today, from prayers for the dead to laughter in costume-clad streets, Halloween speaks of humanity’s timeless need to face the unknown with imagination and joy.

As the October night deepens and children’s laughter mingles with the whisper of falling leaves, remember: behind every mask is an echo of an ancient fire, still burning bright against the dark

Tag: Featured

-

Halloween: Where myths, masks & magic meet

-

Guru Nanak in the eyes of scholars, spiritual masters

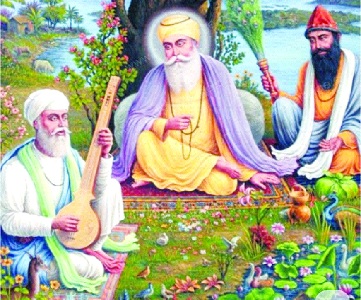

In the vast spiritual landscape of India, few figures command as much reverence, intellectual curiosity, and universal admiration as Guru Nanak Dev Ji-the 15th-century seer whose words became the foundation of Sikhism. More than five centuries later, Nanak’s luminous teachings continue to stir minds and hearts across traditions, drawing reflections not only from his followers but also from spiritual masters, philosophers, and historians across the world. From Osho Rajneesh and the Dalai Lama to modern historians like W.H. McLeod, each has seen in Nanak a mirror reflecting their own quest for truth, harmony, and social transformation.

Among modern spiritual teachers, Osho Rajneesh spoke of Guru Nanak with deep affection and awe. To Osho, Nanak was not merely a preacher but a poet of the divine, a singer who expressed cosmic truths through rhythm and melody.

“Nanak’s path to realization,” Osho once said, “is not dry philosophy but a song filled with fragrance and joy. His way is music, not asceticism.”

In his discourses on the Japji Sahib, Osho interpreted Nanak’s words as the first outpouring of divine union-the spontaneous poetry of enlightenment. He described Nanak as a mystic who bridged earth and sky through his hymns, whose “Naam” (the divine Name) was both the path and the destination.

“When the ego disappears,” Osho wrote, “whatever stands before your eyes is God Himself. Nanak saw this and sang it.”

For Osho, Nanak symbolized the freedom of the spirit-a soul that transcended dogma, uniting Hindu and Muslim, philosophy and devotion, silence and song.

The 14th Dalai Lama, the global voice of Buddhist compassion, has often spoken of his admiration for Guru Nanak Dev Ji. On the 550th birth anniversary celebrations of the Guru, His Holiness said:

“I admire Guru Nanak, who came from a Hindu background, for making a pilgrimage to Mecca as an expression of respect. His life is a message of harmony among all faiths.”

The Dalai Lama finds in Nanak’s life an embodiment of karuna-compassion that transcends boundaries. He has called the Sikh community “an example for the modern world,” praising their work ethic and generosity:

“Among the Sikhs,” he noted, “there are hardly any beggars. You are not only hard-working but also generous in helping one another. Guru Nanak’s teachings of equality and selfless service are what the world needs today.”

To the Dalai Lama, Nanak stands as a spiritual bridge-builder, a saint who lived the essence of interfaith respect long before such terms existed. His message of compassion and selfless action aligns seamlessly with Buddhist principles of loving-kindness and mindfulness.

According to Swami Vivekananda: “There was a great prophet in India, Guru Nanak … He conferred with Hindus and Mohammedans, and tried to bring about a new state of things.”

Rabindranath Tagore said: “The freedom that Baba Nanak had felt was not political freedom; his sense of dharma was not constricted by the worship of deities that was limited to a certain country’s or people’s imagination and habit, and did not accommodate the universal human heart… he dedicated his life to preaching that freedom to all.” Tagore recalled his childhood visit to the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) in Amritsar and wrote: “I remember the Gurudarbar at Amritsar like a dream. … My father would sit among those Sikh worshippers …”

On Nanak’s hymn-“aarti” (Gagan Mai Thaal) Tagore said: “Asked to compose an anthem for the entire world, that had already been done long ago by Guru Nanak.”

In a prayer meeting speech (New Delhi, 26 Sept 1947) Mahatma Gandhi said: “Sikhism started with Guru Nanak. What did Guru Nanak teach? He said that God is known by several names including Allah, Rahim, Khuda. … Nanak Sahib tried to bring together all religions.”

While spiritual masters view Guru Nanak through the eyes of love and devotion, historians and scholars approach him with a different kind of reverence-through research, analysis, and interpretation.

Swami Sivananda of the Divine Life Society, said: “Guru Nanak is a great prophet of Peace. Guru Nanak’s teaching breathes the purest spirit of devotion… He takes the view of the Upanishads that there is one Brahman.”

Several of Paramahansa Yogananda’s self-realization hymn collections reference Guru Nanak’s devotional lines (e.g., translations/adaptations of Nanak’s chants such as “He Hari Sundara / O God Beautiful” appearing in collections attributed to Yogananda followers).

Contemporary Aurobindo Society posts and tributes commemorate Guru Nanak’s call to unity and humanity:

Sant-poets such as Kabir and Ravidas are often invoked together with Nanak in devotional/poetic dialogues. Traditional janamsakhi-style stories present mutual respect among these sants; modern retellings present Nanak praising Kabir’s “nij baani” and vice versa.

The pioneering New Zealand historian W.H. McLeod, in his landmark study Guru Nanak and the Sikh Religion, examined Nanak as a historical and religious innovator. McLeod applied critical methods to the traditional Janamsakhis (biographical legends) and argued that Nanak’s message belonged to the Sant tradition of northern India, emphasizing inner devotion over ritual. Though McLeod’s approach was groundbreaking, it also sparked debates within Sikh circles for what some saw as an over-secular reading of Nanak’s spirituality.

Sadhguru speaks of Guru Nanak as a spiritual master who lived from an “inner experience of life” rather than through scriptures. He emphasizes Guru Nanak’s compassionate and courageous nature, noting that he was not always gentle but knew when to be hard and when to be soft. Sadhguru highlights the story of the “heavenly needle” to illustrate that Guru Nanak’s life was not about amassing possessions, but about living from a place of inner spaciousness and realizing life itself.

A Pioneer of Universal Humanism: Scholars view Guru Nanak’s philosophy as a “liberating philosophy of universal humanism,” advocating liberty, love, respect, justice, and equality for all. He is recognized for questioning and condemning social customs and religious practices that discriminated against people based on caste, creed, or gender.

Original Metaphysical Thought: While his ideas derived in part from the Sant and Bhakti traditions, scholars argue that the fundamental issues of Sikhism are “fundamentally different in substance and direction,” and his metaphysical aspects are considered original, not merely syncretic.

Rejection of Ritualism and Asceticism: Academic experts highlight his pragmatic approach to spirituality. He rejected idol worship, the caste system, and the idea of asceticism or renouncing the world, advocating instead for a “householder’s life” combined with spiritual practice and honest labor (Kirat Karni).

Emphasis on Truthful Living: Scholars emphasize that for Guru Nanak, “truth is a high ideal, higher still is truthful living”. His teachings are seen as a call to action for creating a just society, not just a guide for personal salvation in the afterlife.

A Poet and Mystic: Guru Nanak is also recognized as a poet of “uncommon sensitivity” and a “wonderful mystic” whose verses, compiled in the Guru Granth Sahib, communicate complex spiritual ideas in simple language accessible to the common person.

“Hindu ka Guru, Musalman ka Pir”: This popular saying reflects how he was, and still is, revered by both Hindus and Muslims, who saw him as their own teacher and spiritual guide.

Baha’i Faith: The Universal House of Justice of the Baha’i Faith considers Guru Nanak to have been endowed with a “saintly character” and views him as a “saint of the highest order” who was divinely inspired to reconcile the conflicts between Hinduism and Islam.

Ahmadiyya Muslim Community: This community considers Guru Nanak to have been a Muslim saint who sought to educate people about the real teachings of Islam.

A Light for All Ages

Five hundred years after his birth, Guru Nanak continues to illuminate the human quest for truth and peace. His hymns still resound in gurdwaras and homes across the world, his ethics still shape communities, and his message still speaks to the global heart weary of division -

Gurdwaras associated with Guru Nanak: The sacred footsteps of the first Sikh Guru

When one traces the luminous journey of Guru Nanak Dev Ji-the founder of Sikhism and the voice of divine unity-one does not just follow a life, but an eternal light that continues to illuminate millions. His message of “Ek Onkar” — the oneness of the Creator-resonated across mountains, deserts, and seas. During his lifetime, Guru Nanak undertook extensive travels, known as Udasis, to spread the universal message of truth, equality, compassion, and devotion. Across these journeys, sacred shrines-Gurdwaras-arose at places touched by his divine presence. Today, these gurdwaras stand as living chronicles of his teachings, faith, and humanity.

Let us journey through some of the most revered Gurdwaras associated with Guru Nanak Dev Ji, each narrating a story of spiritual transformation and timeless wisdom.

Gurdwara Nankana Sahib

The sacred town of Nankana Sahib, near Lahore in present-day Pakistan, holds unparalleled reverence as the birthplace of Guru Nanak Dev Ji in 1469. Originally known as Talwandi, it was later renamed Nankana Sahib in his honor. The main shrine, Gurdwara Janam Asthan, stands where the divine infant was born to Mehta Kalu and Mata Tripta. The serene complex includes shrines marking significant events of his early life-the sacred well from which his sister Bebe Nanaki drew water, and the site where young Nanak amazed the village priest by composing hymns in praise of the One Creator. Every year, Guru Nanak Gurpurab witnesses thousands of devotees gathering here, transcending borders in devotion and unity.

Gurdwara Panja Sahib

Nestled against the Margalla Hills, this gurdwara marks one of the most miraculous events in Guru Nanak’s life. When the local saint Wali Qandhari refused to share water with thirsty travelers, Guru Nanak caused a spring to emerge by lifting a rock. Wali Qandhari, enraged, hurled a boulder down the hill, but Guru Nanak stopped it with his hand-leaving his divine palm imprint (Panja) upon the stone. The gurdwara, built around this sacred rock, is now one of Sikhism’s holiest pilgrimage sites, symbolizing humility’s triumph over arrogance and the Guru’s infinite compassion.

Gurdwara Darbar Sahib, Kartarpur

Kartarpur Sahib holds a sanctity unlike any other, for it was here that Guru Nanak spent the last 18 years of his life in spiritual reflection and service. He tilled the land, established the first Sikh commune (Kartarpur meaning “Creator’s Town”), and taught the principles of honest living, Naam Simran (meditation on God’s name), and Kirat Karo (earn by honest means). Guru Nanak’s spirit of equality flourished here-Hindus and Muslims ate together in the Langar and prayed in unison. After his passing in 1539, both communities built memorials side by side, and today the magnificent Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur-accessible through the Kartarpur Corridor-stands as a beacon of peace between India and Pakistan.

Gurdwara Ber Sahib

At Sultanpur Lodhi, Guru Nanak’s spiritual awakening unfolded. While working as a storekeeper for the Nawab Daulat Khan, Nanak would spend hours immersed in divine contemplation. One dawn, he went to bathe in the Kali Bein rivulet and disappeared for three days. Upon returning, he proclaimed, “Na koi Hindu, na Musalman”-there is neither Hindu nor Muslim, only the One Divine. The sacred Ber tree under which he rested still stands at Gurdwara Ber Sahib, making it one of the most significant pilgrimage sites for Sikhs. Every Gurpurab, Sultanpur Lodhi transforms into a radiant sea of devotion.

Gurdwara Dera Baba Nanak

Just across the border from Kartarpur lies Gurdwara Dera Baba Nanak, built at the site where Guru Nanak once meditated and later settled with his family before establishing Kartarpur. The gurdwara overlooks the Ravi River, and from its upper floors, devotees can view Kartarpur Sahib through telescopes-a vision that evokes deep emotion and longing. The annual Kartarpur Sahib Jor Mela sees pilgrims gathering in remembrance of the Guru’s last years.

Gurdwara Nanak Jhira Sahib

Far to the south, in Bidar, lies a shrine that bears witness to Guru Nanak’s compassion. When he found the town suffering from water scarcity, he miraculously caused a spring-Jhira-to gush forth from the hillside. The pristine water flows even today, symbolizing purity and grace. The gurdwara’s architecture blends Sikh simplicity with Deccan artistry, attracting pilgrims from across India, especially during Guru Nanak Jayanti celebrations.

Gurdwara Pathar Sahib

Amid the rugged Himalayas, Gurdwara Pathar Sahib stands as a reminder of Guru Nanak’s journey to Tibet. According to legend, a demon attempted to crush the Guru with a boulder while he meditated. Miraculously, the rock softened, leaving his body’s impression intact while repelling the demon’s attack. The site, maintained by the Indian Army, is visited by both soldiers and travelers who find solace in its calm, high-altitude serenity-a meeting point of faith and fortitude.

Gurdwara Lakhpat Sahib

During his western Udasi, Guru Nanak visited Lakhpat-a once-thriving port city in Gujarat-on his way to Mecca and Medina. The gurdwara here preserves his wooden footwear, palki (palanquin), and handwritten manuscripts. The place reverberates with the Guru’s message that true pilgrimage lies not in travel alone, but in spiritual awakening. Lakhpat Sahib is a UNESCO-protected heritage site, symbolizing Guru Nanak’s global message of harmony.

Gurdwara Mattan Sahib

In the picturesque valley of Kashmir, Guru Nanak conversed with local Hindu priests and Sufi mystics at Mattan, emphasizing that true devotion is not bound by rituals but by inner purity. The gurdwara built here retains a sacred pond and stone slabs where the Guru is believed to have meditated, marking the northernmost trail of his spiritual journey.

A Tapestry of Faith Across Continents

From Nankana to Leh, from Bidar to Lakhpat-Guru Nanak’s footprints span the length and breadth of South Asia, echoing his timeless message of “Sarbat da Bhala”-the welfare of all. Each gurdwara dedicated to his memory is not merely a structure of stone and marble, but a living symbol of his universal vision: that all humanity is one, and service to others is service to God.

These shrines are not museums of the past; they are pulsating centers of spiritual vitality, where the hymns of the Guru Granth Sahib continue to resound, and where the fragrance of Langar unites rich and poor alike. As we bow our heads at these sacred sites, we are reminded that Guru Nanak’s journey never ended-it continues within every seeker who walks the path of truth, humility, and love. -

Guru Nanak and the birth of Sikh spirit of resistance

The 15th century was a time of darkness across much of northern India. Empires rose and fell, and ordinary people bore the weight of both – crushed under oppressive rulers, heavy taxes, and the violence of foreign invasions. Fear and fatalism ruled the hearts of many; religion had become ritual, and injustice went unchallenged.

It was in this age of despair that Guru Nanak Dev Ji (1469-1539) – the first Sikh Guru and founder of Sikhism – rose as a radiant voice of conscience. His message was not confined to temples or mosques; it was a clarion call for freedom of the human spirit.

When the Mughal invader Babur swept across India with his armies, leaving cities ravaged and people enslaved, Guru Nanak refused to stay silent. He witnessed the atrocities with a heart full of compassion – and anguish. But instead of submitting or turning away, he confronted the conqueror through verse, with the piercing power of divine truth.

“Eti maar payee kurlane, tai ki dard na aaya” – Did You Not Feel Their Pain?

In his composition known as the Babarvani (recorded in the Guru Granth Sahib, pages 360-363), Guru Nanak cried out in protest:

These lines were not merely a lament – they were a rebuke to both the temporal and divine order. Nanak addressed the Almighty but indicted the emperor; his question pierced through the sanctity of power and privilege.

Here was no saint removed from the world – Guru Nanak was the first spiritual master in Indian history to openly challenge a sovereign for cruelty to his subjects. He denounced tyranny not as a political act, but as a spiritual duty. His protest was rooted in the conviction that where there is oppression, God Himself is defiled.

The Birth of the Sikh Spirit of Resistance

From that moment, the spirit of resistance – grounded in righteousness, not revenge – became woven into the Sikh soul.

Guru Nanak’s defiance was not an act of rebellion for power, but of compassion for humanity. He awakened in his followers the courage to say no – no to tyranny, no to inequality, no to fear.

His legacy was not one of ascetic withdrawal but of engaged spirituality – a faith meant to stand with the oppressed and speak truth to power.

From Word to Sword: The Lineage of Courage

That seed of defiance, planted by Guru Nanak, blossomed through the ten Sikh Gurus who followed.

Guru Hargobind Sahib (1595-1644)

The sixth Guru, Guru Hargobind, transformed the spiritual resistance of Nanak into organized strength. He donned two swords – Miri and Piri, representing temporal and spiritual sovereignty.

He taught that the saint must also be a soldier when righteousness is threatened. When imprisoned by Emperor Jahangir, Guru Hargobind refused to accept freedom unless 52 Hill Rajas – fellow prisoners of conscience – were released with him. This episode, remembered as Bandi Chhor Diwas, became a lasting symbol of liberation and justice.Guru Tegh Bahadur (1621-1675)

Two generations later, Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji, the ninth Guru, carried Nanak’s spirit of defiance to its ultimate expression. When Emperor Aurangzeb began forcibly converting Hindus to Islam, Guru Tegh Bahadur stood as their shield.

He was imprisoned, tortured, and ultimately executed in Delhi for defending freedom of faith – not just for Sikhs, but for all.

His sacrifice, remembered as Hind di Chadar – the Shield of India – exemplified Guru Nanak’s vision of universal justice.

Guru Gobind Singh Ji (1666-1708)

The Tenth Master, Guru Gobind Singh Ji, completed the evolution of Nanak’s message from word to action. In 1699, he created the Khalsa, a brotherhood of the pure, armed with both sword and spirit, to uphold truth and protect the oppressed.

His declaration –

“When all other means have failed, it is righteous to draw the sword” –

was not a call to conquest, but to moral resistance. Through him, Nanak’s spirit of fearless compassion became an institution – a way of life.

Beyond the Gurus: The Flame That Never Died

After Guru Gobind Singh, the spirit of Guru Nanak continued to inspire countless acts of courage.

– Banda Singh Bahadur, a disciple of Guru Gobind Singh, led an uprising against Mughal tyranny, redistributing land to the poor and establishing the first Sikh rule based on justice.

– In the 18th century, Sikh warriors resisted persecution under successive Mughal and Afghan invasions, forming the Khalsa Misls that later united into the empire of Maharaja Ranjit Singh – a reign known for religious tolerance and equality.

– During the Indian freedom struggle, Sikhs made up a small fraction of India’s population yet contributed disproportionately to its martyrs – from Udham Singh, who avenged the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, to countless unsung heroes of the Ghadar and Akali movements.

– Even today, Sikhs around the world embody this same courage – standing at the forefront of humanitarian crises, offering Langar to refugees and the hungry, standing up against injustice wherever it arises.

A Unique Contribution to the World’s Spiritual Heritage

Guru Nanak’s protest against Babur was not simply a political act – it was a spiritual milestone in human history.

Until then, saints had often turned away from worldly suffering. Nanak turned toward it – bringing divine light into the darkest corners of society.

His was the first spiritual revolution in India to unite faith with social responsibility, devotion with defiance, prayer with protest. He showed that the Divine is not distant but deeply involved in the struggle for justice.

This moral courage – this union of compassion and resistance – became the hallmark of Sikh identity.

To this day, the Sikh stands tall – humble in service, but fearless in defense of the weak – carrying forward Guru Nanak’s legacy of speaking truth to power, even at the cost of life itself -

The living word: How Guru Nanak’s voice became the eternal Guru

More than five centuries ago, amid the fields of Punjab and the tumult of empires, a simple man with a luminous vision began to sing. His words were not sermons but songs – flowing like rivers from the depths of divine realization.

That man was Guru Nanak Dev Ji (1469-1539), the founder of Sikhism – a saint, poet, philosopher, and reformer who spoke of oneness beyond religion, of truth beyond ritual, of humanity beyond caste.

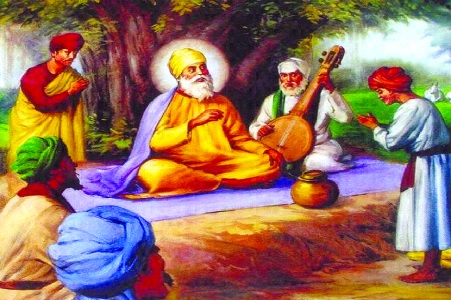

But Guru Nanak did not merely preach. He composed Shabads – sacred verses – that carried the vibration of the Infinite. Each word was a drop from the ocean of his enlightenment. These verses, sung with his companion Bhai Mardana on the rabab, became the living heartbeat of a new spiritual path – the Sikh way of devotion, equality, and service.

Today, those very words live on in the Guru Granth Sahib, the eternal scripture and spiritual guide of the Sikh faith. It is not just a book, but a living embodiment of the Guru’s consciousness – the eternal light (Jyot) passed from Guru Nanak to all who seek truth.

From Guru’s Lips to Living Scripture

Guru Nanak’s compositions were collected and preserved by his disciples, forming the earliest body of Sikh hymns known as Bani. These verses were not confined to any single language – he used Punjabi, Persian, Sanskrit, Braj, and Marathi – reflecting his universal message that the Divine speaks in every tongue.

When the fifth Guru, Guru Arjan Dev Ji, compiled the Adi Granth in 1604, he placed Guru Nanak’s hymns at its heart. He also included the verses of other Sikh Gurus and of saints from diverse backgrounds – Hindu bhaktas like Kabir and Namdev, and Muslim mystics like Sheikh Farid and Bhagat Ravidas. This inclusivity was itself a declaration: truth is not owned by any one faith.

The Guru Granth Sahib thus became not just the scripture of the Sikhs, but a universal chorus of divine voices – a collective song of humanity seeking the One.

The Guru Lives in the Word

In 1708, before leaving his physical form, Guru Gobind Singh Ji, the tenth Sikh Guru, bestowed the Guruship upon the Guru Granth Sahib, declaring:

“Sab Sikhan ko hukam hai, Guru manyo Granth.”

(“To all Sikhs, the command is: Recognize the Granth as your Guru.”)

With this act, the line of human Gurus ended, and the living spirit of the Guru continued in the form of the sacred word. From that moment on, the Guru Granth Sahib became the eternal, guiding presence for the Sikh community – revered not as a text, but as the living Guru itself.

To this day, Sikhs bow before the Guru Granth Sahib not in idolatry, but in reverence to divine wisdom – acknowledging that the same light which shone in Guru Nanak shines through these words.

Each hymn, each page, each verse is not read but experienced – sung in kirtan, contemplated in Simran, and lived through Seva.

Seva: The Living Legacy of the Guru

If the Guru Granth Sahib is the spiritual heartbeat of Sikhism, Seva (selfless service) is its pulse – the practical expression of the Guru’s teaching.

Guru Nanak taught that true worship is not in ritual, but in serving others as a form of serving God. He said:

“Truth is high, but higher still is truthful living.”

That truth comes alive in every Sikh who offers food in a Langar, carries water for pilgrims, or volunteers in hospitals and disaster zones. From feeding the hungry during global crises to rebuilding homes after floods and earthquakes, Sikhs across the world embody Nanak’s message that the Divine resides in every being.

Seva is not charity – it is equality in action. When one kneels to wash another’s feet, or serves a stranger food in the Langar hall, there is no giver and no receiver – only the One acting through many.

In this way, the word of the Guru becomes flesh through service. The verses of the Granth are not merely recited; they are lived in kitchens, fields, relief camps, and homes across the world.

The Music of the Infinite

Guru Nanak’s words were never meant to be read silently – they were meant to be sung. The Guru Granth Sahib is organized by ragas (musical measures), each designed to evoke a spiritual emotion.

From the dawn melody of Asa di Var, awakening hearts to gratitude, to the serene tones of Rehras Sahib at dusk, these hymns create a rhythm of remembrance throughout the day.

Wherever the kirtan (devotional singing) flows – whether in a small village Gurdwara or at the Golden Temple in Amritsar – it carries the same vibration: the call to awaken to the One.

This sound current (Naad) is itself a form of Seva – for when one sings from the heart, one uplifts others in love and unity.

The Eternal Message: Ik Onkar

At the heart of the Guru Granth Sahib lies the opening verse – the Mool Mantar, revealed by Guru Nanak:

“Ik Onkar, Satnam, Karta Purakh, Nirbhau, Nirvair…”

(“There is One Creator, whose name is Truth, the Creator without fear or enmity…”)

These few lines contain the essence of Sikh philosophy – a universal spiritual declaration that transcends creed and culture.

It tells us that the Divine is not a deity belonging to one faith, but the underlying essence of all that exists – beyond gender, beyond form, beyond division.

That vision continues to guide millions today – from temples and mosques to meditation halls and interfaith movements – wherever people seek the truth of unity in diversity.

The Word That Walks the Earth

In every Gurdwara, the Guru Granth Sahib is not kept on a shelf but enthroned, covered with silken cloths, fanned with devotion, and carried in procession like a living master.

When opened each morning (Prakash) and closed at night (Sukhasan), it symbolizes the rising and resting of divine wisdom in daily life.

In these rituals, the Sikh community does not worship paper and ink – it honors the eternal consciousness that flows through those words.

Each reading from the Granth, called a Hukamnama, is taken as divine guidance for the day – a dialogue between the Infinite and the human heart.

And in every act of Seva – whether it is cleaning the Gurdwara floor, planting trees, or serving Langar – the words of the Guru Granth Sahib find their truest expression.

A Light for All Humanity

Guru Nanak’s vision was never limited to one community. He spoke for all seekers who longed for truth and justice, love and liberation.

The Guru Granth Sahib, compiled from voices across religions and castes, stands as a monument to the universality of the human spirit.

Today, when one listens to the shabads being sung at dawn in Amritsar, or watches Sikh volunteers feeding thousands at airports and disaster zones, one witnesses something profound:

The Guru still lives – not as a figure of the past, but as a living light in the present. That light shines through every act of Seva, every song of devotion, every humble offering to humanity.

The Guru Is Still Speaking

Five centuries after Guru Nanak walked the earth, his voice continues to echo – in the rhythmic recitation of Japji Sahib, in the laughter of children serving Langar, in the silence of meditation.

The Guru Granth Sahib is not history; it is living presence.

Every word is a spark of eternity.

Every act of Seva is a verse in motion.

And together, they remind us of what Guru Nanak came to teach:

That there is no separation between God and creation, no wall between prayer and action –

only the radiant truth that the Divine lives in every heart and every deed.

“As fragrance abides in the flower, and reflection in the mirror – so does the Divine dwell in all.” — Guru Nanak Dev Ji -

Guru Nanak: The mystic poet who redefined spiritual freedom

In a world overwhelmed by conflict, inequality, and disconnection, the words of a poet from 15th-century Punjab still offer astonishing clarity.

That poet was Guru Nanak Dev Ji (1469-1539) – the founder of Sikhism, a spiritual visionary whose hymns transcend time, creed, and geography.

He was not a prophet seeking followers, nor a reformer craving power. He was a seer of truth, a poet of the soul, and a philosopher of the human condition – who saw the Divine not in distant heavens but in the rhythm of everyday life.

His poetry, composed in the musical cadence of raag (melody), became a bridge between God and humanity – a living song that continues to guide millions through the Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikh scripture.

The Poet Who Sang the Universe

Guru Nanak’s poetry was unlike anything the subcontinent had ever heard. It spoke not of ritual or hierarchy, but of experience – the direct encounter with the Infinite.

In his opening verse, the Mool Mantar, he distilled the essence of existence into a few immortal lines:

“Ik Onkar, Satnam, Karta Purakh, Nirbhau, Nirvair…”

There is One Eternal Reality; Truth is Its Name; It is the Creator, without fear or enmity.

Every word radiates universality. In those few syllables, Guru Nanak erased the boundaries that divided man from man, religion from religion, self from the Divine.

His poetry did not describe God; it revealed oneness as a lived experience. For him, the cosmos itself was music – every being a note in the divine song of creation.

Guru Nanak’s journey was one of inquiry, not dogma. From childhood, he questioned blind faith and hollow ritual. When asked to wear the sacred thread that signified caste, he refused, asking:

“Make compassion the cotton, contentment the thread, and truth the knot – that is the sacred thread that never breaks.”

This poetic defiance carried a profound philosophical truth: spirituality is not inherited, it is earned through consciousness.

Throughout his life, Guru Nanak challenged systems that divided humanity – caste hierarchies, religious exclusivism, and gender inequality. His question was simple yet seismic:

“If all are born of the same Light, who is high and who is low?”

In an age where religion was often used as an instrument of control, Guru Nanak redefined it as a path to liberation through Naam (divine remembrance), Kirat (honest living), and Vand Chhakna (sharing with others).

He was both philosopher and reformer – merging metaphysics with social ethics, contemplation with action.

A Universal Thinker Before His Time

Long before the Enlightenment or modern humanism, Guru Nanak articulated a universalist philosophy that resonates deeply with the 21st century. He rejected religious exclusivity centuries before interfaith dialogue became fashionable. His belief that “God has many names, but the Light is one” speaks powerfully in our polarized times.

He envisioned a world without borders – of Sarbat da Bhala – the well-being of all. In an age obsessed with personal gain, this principle offers a moral compass rooted in empathy and collective upliftment.

His environmental insight was equally prophetic. In the Japji Sahib, he described air as the teacher, water as the father, and earth as the mother – a worldview that sees nature not as a resource but as kin.

“Pavan guru, pani pita, mata dharat mahat.”

Air is the Guru, water the father, and great earth the mother.

Centuries before the climate crisis, Guru Nanak understood that harmony with nature was harmony with the Divine.

The Relevance of Nanak’s Thought Today

Guru Nanak’s teachings address every crisis of our age – moral, ecological, and existential.

In an age of inequality, his message of oneness reminds us that no faith, gender, or race is inferior.

In an age of greed, his call for honest work (Kirat Karna) reaffirms the dignity of labour. In an age of anxiety, his principle of remembrance (Naam Japna) offers inner stillness amidst chaos. In an age of isolation, his teaching of sharing (Vand Chhakna) rebuilds community.

For a divided and restless planet, his words offer a path not backward into tradition, but forward into truth – a spiritual humanism rooted in awareness and compassion.

The Rhythm of Eternity:

Nanak’s Poetic Legacy

Guru Nanak’s compositions were not essays of philosophy but songs of realization. Each Shabad (hymn) was meant to be sung, felt, and lived. His companion, Bhai Mardana, would play the rabab as the Guru’s words flowed – transforming spiritual truth into sound, meditation into melody.

The Guru Granth Sahib, which contains 974 hymns of Guru Nanak, remains the world’s only scripture written entirely in poetic and musical form. Each hymn is placed under a specific raag, signifying the mood and emotion of divine experience.

This fusion of art and spirituality makes his philosophy accessible not just to the intellect, but to the heart. As long as there is music, Guru Nanak’s message will live – because his truth is sung, not spoken.

The Philosopher of Courage and Compassion

Guru Nanak was not merely a contemplative thinker – he was a moral rebel. When tyrants like Babur invaded India, causing immense suffering, Nanak raised his voice in divine protest.

“Eti maar payee kurlane, tai ki dard na aaya?”

Such cries of pain are heard, O Lord – did You not feel compassion?

It was perhaps the first poetic indictment of tyranny in Indian history – a saint confronting an emperor through song.

From that fearless moral inquiry was born the Sikh tradition of Sant-Sipahi – the saint-soldier who defends righteousness while remaining anchored in compassion.

Guru Nanak: For Every Seeker

Five hundred years on, Guru Nanak remains a teacher not bound by religion. His words speak to the monk and the activist, the scientist and the artist, the skeptic and the believer.

They do not ask for conversion – only for consciousness.

When he says, “Truth is high, but higher still is truthful living,”

he invites us to live our ethics, not merely preach them.

When he says, “See the light of God in all and never forget the One who dwells in all hearts,”

> he offers a solution to every conflict – the recognition of shared divinity.

Guru Nanak’s philosophy was never meant for a temple, but for life itself – to be lived in the marketplace, the home, the field, and the heart.

The Eternal Relevance

Half a millennium later, the world still struggles with the very divisions Guru Nanak sought to dissolve – inequality, intolerance, greed, and alienation. Yet his voice endures, as fresh and fearless as the day it first echoed along the banks of the River Bein.

To read Guru Nanak is to rediscover what it means to be human.

To sing his words is to awaken the soul to unity.

And to live his philosophy is to walk the timeless path of compassion – the path that leads from self to the infinite.

The Poet Who Became the Voice of the Eternal

Guru Nanak was a poet, yes – but not one who wrote for fame or empire.

He was a poet of awakening, whose verses still dissolve barriers and speak to the heart of a world in need of healing.

He was a philosopher without a school, whose thought continues to resonate with mystics, scholars, and seekers across cultures.

And above all, he was – and remains – a Guru for all humanity, a reminder that the truest wisdom is not in renouncing the world, but in redeeming it. -

Kartarpur: The village of eternal light

On the banks of the serene River Ravi, in the fertile plains of Punjab, lies a village whose name means “The Abode of the Creator” – Kartarpur.

It was here, more than five centuries ago, that Guru Nanak Dev Ji, the founder of Sikhism, settled after his long journeys across Asia. And it was here, among farmers and seekers, that he planted not only crops, but the seeds of a timeless philosophy – of truthful living, equality, service, and divine oneness.

Today, Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur stands as a beacon of that vision – a sacred site where history, faith, and humanity converge. It is both a place of pilgrimage and a powerful symbol of hope and reconciliation in a world still learning to embrace unity beyond borders.

The Guru’s Return

After traveling for over 25 years on his four great Udasis, spreading the message of Ik Onkar – the Oneness of all existence – Guru Nanak chose to spend the last 18 years of his life in Kartarpur (now in Pakistan’s Narowal district).

In the year 1522, he built a modest settlement on the Ravi’s banks. Unlike the hermits who sought solitude in mountains, Nanak chose the earth itself as his temple. He tilled the land, sowed seeds, and lived as a humble farmer – proving that spirituality and honest work (Kirat Karna) are not separate paths but one.

“Truth is high,” he said, “but higher still is truthful living.”

In this village, spirituality took on a practical form. The community ate together, prayed together, worked together – the earliest form of Sangat and Pangat (holy congregation and equality in service). Kartarpur became a living experiment in divine democracy, where no one was rich or poor, high or low.

The First Sikh Commune

Kartarpur was not merely a settlement; it was the first Sikh commune, a model of what society could be when guided by compassion instead of caste, by humility instead of hierarchy.

Here, the Langar (community kitchen) – a revolutionary idea introduced by Guru Nanak – became a daily practice. Men and women cooked and served together, transcending social barriers that had divided India for centuries.

The Guru composed hymns of universal truth, many of which would later form the heart of the Guru Granth Sahib. His close companion, Bhai Mardana, played the rabab as Nanak sang of the Creator’s presence in every leaf, every breath, every moment of existence.

The Passing of the Eternal Light

In 1539 CE, as the Guru’s earthly life came to an end, legend says that a debate arose between his Hindu and Muslim followers over his final rites. The Hindus wished to cremate him; the Muslims wanted to bury him.

When they lifted the sheet covering his body, they found only fresh flowers in place of his mortal form.

Each group took half – one buried, one cremated – symbolizing that Guru Nanak belonged to all humanity.

To this day, both a samadhi (Hindu memorial) and a maqbara (Muslim tomb) stand side by side at Kartarpur – silent witnesses to a truth that transcends religion.

The Gurdwara: A Living Memorial of Peace

Over the centuries, Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur became one of Sikhism’s holiest shrines. The white domes rise gracefully above green fields, the structure gleaming under the Punjab sun like a reflection of the divine light Nanak spoke of.

From its verandas, one can still see the River Ravi flowing – the same waters where the Guru once walked, prayed, and worked. Pilgrims describe the place as charged with peace, as if time itself pauses in Kartarpur, and the air still hums with the sound of Nanak’s hymns.

Kartarpur Corridor: Bridge Across Borders

For seven decades after the partition of India in 1947, this sacred site remained separated from millions of devotees by a line drawn through Punjab’s heart. Many Sikhs could only stand at the Indian border near Dera Baba Nanak and gaze across the fields, their eyes moist with longing for the shrine just 4 kilometers away.

Then, in November 2019, a miracle unfolded. On the 550th birth anniversary of Guru Nanak, India and Pakistan inaugurated the Kartarpur Corridor – a visa-free passage allowing pilgrims from India to visit the shrine across the border.

It was an extraordinary moment in modern history – a corridor of faith beyond politics, built on the Guru’s own vision of peace and coexistence.

“Let no walls divide those who share the same divine light,” Guru Nanak had once said – and Kartarpur today stands as a living realization of those words.

A Symbol of Hope in a Divided World

The Kartarpur Corridor is more than a road; it is a pathway of reconciliation.

In an age where religion often divides, this narrow stretch of land reminds humanity of what we can build when we remember the teachings of those who saw no “other.”

Pilgrims of all backgrounds – Sikhs, Hindus, Muslims, even international travelers – walk barefoot on its marble floors, share meals in the Langar hall, and feel the same serenity. For many, the visit becomes a spiritual homecoming – not to a religion, but to a sense of oneness and belonging.

Echoes of Guru Nanak’s Vision

Kartarpur in the Modern Spirit

In recent years, the image of pilgrims walking across the corridor – some elderly, some in tears, many carrying soil from the shrine in small pouches – has become an emblem of faith uniting where politics divides.

International peace advocates often cite Kartarpur as a model for interfaith cooperation, a sacred geography where devotion transcends nationalism.

Scholars call it “a moral corridor” – an open invitation to rediscover Guru Nanak’s universal spirituality in our time of fragmentation.

The Village That Still Teaches the World

Standing at Kartarpur, one can still hear the echo of Guru Nanak’s eternal words:

“There is One Light in all creation; By that Light, all are born.”

The Ravi still flows gently by, reflecting both sun and moon – as if to say that duality is only illusion. The fields still bloom with the crops of service and humility. And the white domes of Darbar Sahib still gleam like lanterns of peace in the night.

Kartarpur is not just a place on a map – it is a metaphor for humanity’s highest calling.

It tells us that the boundaries that divide hearts can be crossed not with weapons or walls, but with faith, forgiveness, and love.

The Eternal Light Lives On

As pilgrims bow their heads at the shrine where Guru Nanak spent his final days, they do not just remember a saint – they experience a truth.

The same truth he lived, sang, and sowed in these fields: that God is One, humanity is one, and the light within us is eternal. Five centuries have passed, but in the quiet of Kartarpur, one still feels the presence of the man who once walked here – the farmer-saint, the poet of peace, the messenger of Oneness -

Beyond religion: Guru Nanak’s universal spirituality

When Guru Nanak Dev Ji walked the earth more than five centuries ago, the Indian subcontinent was a landscape divided by faith, caste, and ritual. The air trembled with chants from temples and mosques – yet humanity was lost in its noise. In that age of confusion, Guru Nanak’s voice rose not as a preacher of a new creed, but as the awakener of a timeless truth – that the Divine is not confined to one religion, scripture, or path.

His vision was not about creating another sect, but about dissolving barriers. Guru Nanak’s universal spirituality continues to inspire Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, Christians, and seekers of every path – a reminder that all rivers flow to the same ocean.

The Dawn of a New Consciousness

Born in 1469 in Talwandi (now Nankana Sahib, Pakistan), Nanak grew up in a time of social unrest. The Mughal Empire was rising, sectarian conflicts were common, and spiritual life was buried beneath ceremony and dogma. Yet, young Nanak questioned everything – the rituals, the divisions, the arrogance of religious institutions.

One morning, after disappearing into the waters of the Kali Bein at Sultanpur Lodhi, he re-emerged transformed – radiant with realization. His first words were:

“There is no Hindu, there is no Muslim – all are children of the One Creator.”

That was not a declaration of rebellion, but of revelation – an awakening to Ik Onkar, the One Divine Reality pervading all existence. From that moment on, Nanak’s life became a journey – not to convert others, but to awaken them to their inner truth.

Ik Onkar: The Sound of Oneness

At the heart of Guru Nanak’s message lies the sacred symbol Ik Onkar, which opens the Sikh scripture, the Guru Granth Sahib. It means:

There is One Reality, One Creator, manifest in all creation.

This was not a philosophical statement – it was a spiritual realization. Nanak saw the Divine not as a distant ruler, but as a living presence in every atom of existence.

In his hymn Japji Sahib, he writes:

“Air is the Guru, Water the Father, and Earth the Great Mother.”

Through these lines, he shattered the boundaries between sacred and secular. Nature itself became holy; service to creation became worship of the Creator. His spirituality was eco-centric, inclusive, and deeply compassionate – centuries before such terms entered modern discourse.

The Dialogue of Faiths: A Universal Vision

Guru Nanak’s four great journeys – the Udasis – took him across India, Tibet, Mecca, Baghdad, and Sri Lanka. In every land, he entered into dialogue, not debate. He met Hindu pandits, Buddhist monks, Jain sages, and Muslim sufis – and in each, he found a reflection of the same divine truth.

Among the Hindus:

He revered the Vedas for their wisdom but rejected blind ritualism and caste hierarchies. “Read the Name of God in your heart, not just on your lips,” he told scholars at Banaras.

Among the Muslims:

He entered mosques, sang the praises of the One, and emphasized submission not to form, but to truth. In Mecca, when rebuked for resting with his feet toward the Kaaba, he gently said, “Turn my feet toward where God is not.” The astonished caretakers found divinity everywhere.

Among the Buddhists and Jains:

He resonated with their ideals of compassion, simplicity, and non-violence, yet cautioned that renunciation alone was not liberation. “Live truthfully amid the world – that is the real asceticism,” he taught.

Among the Sufis:

He shared deep kinship. The Sufi mystics spoke of divine love and unity, and Guru Nanak’s hymns echoed their essence. The Persian saints in Baghdad hailed him as a “Messenger of the One,” recognizing that his God was not a name, but a presence that dwells in every heart.

Beyond Labels: The Human Religion

Guru Nanak’s teachings dismantled the walls of identity. For him, religion was not about belonging to a group, but becoming fully human.

He said:

“Truth is high – but higher still is truthful living.”

To him, devotion meant living with integrity, serving others, and seeing the divine light in all beings. He laid the foundation for a society where no one is high or low, where men and women sit together as equals, and where feeding the hungry (Langar) is holier than fasting in isolation.

His Three Pillars of Sikh Living – Naam Japna (Remembrance of God), Kirat Karna (Honest Work), and Vand Chhakna (Sharing with Others) – remain universal principles that transcend all religions.

Even today, these teachings resonate in Sufi shrines, Hindu ashrams, interfaith gatherings, and humanitarian movements worldwide.

The Universal Voice in Guru Granth Sahib

The Guru Granth Sahib, the living scripture compiled by Guru Arjan Dev Ji, includes hymns not only of Sikh Gurus but also of Hindu Bhaktas and Muslim Sufis – Kabir, Sheikh Farid, Namdev, Ravidas, and others.

This inclusion was no accident; it was the realization of Guru Nanak’s universal vision. It proclaimed that truth is not the monopoly of one community, and that divine wisdom can emerge from any soul devoted to love.

In this way, the Guru Granth Sahib stands as the world’s only interfaith scripture, where saints from diverse backgrounds sing in harmony of the same Eternal One.

Guru Nanak and the Spirit

of Interfaith Harmony

Guru Nanak’s message is not bound to any era – it is an eternal antidote to division. His teachings form the spiritual DNA of interfaith dialogue:

He did not call for the destruction of religions – he sought their purification through love.

He did not reject temples or mosques – he invited humanity to build temples of compassion within their hearts.

He did not ask for conversion – he asked for transformation.

In a world still torn by religious conflict, his life offers a path of reconciliation. He reminds us that faith is not about separation, but about seeing unity in diversity.

A Message for the Modern Seeker

In our century of noise and distraction, Guru Nanak’s voice feels even more relevant. His spirituality is not ritualistic – it is experiential. It does not demand renunciation – it asks for responsible living.

For Buddhists, his emphasis on mindfulness echoes the path of awareness.

For Hindus, his recognition of the formless divine mirrors the Upanishadic spirit.

For Muslims, his insistence on remembrance (Naam Japna) resonates with Zikr. For all humanity, his message is an invitation to look within – to find the One in every heart, and the same light in every being. -

The pilgrim of peace: Guru Nanak’s 4 Udasis

When the Kali Bein at Sultanpur Lodhi released Guru Nanak Dev Ji from its mysterious embrace, he emerged not just as a man transformed, but as a messenger of the Eternal.

That revelation marked the beginning of one of the most extraordinary odysseys in spiritual history – the four great Udasis, or missionary journeys, undertaken by Guru Nanak across India and beyond. Over two decades and tens of thousands of miles, the Guru traversed mountains, deserts, and seas – from the Himalayas to Sri Lanka, from Mecca to Assam – spreading a message that transcended religion, caste, and creed.

Each journey – each Udasi – was not merely travel; it was a pilgrimage of peace, a dialogue with humanity, a revolution of compassion.

The First Udasi (1500-1506 CE): The Awakening of the East

The first journey took Guru Nanak eastward from Punjab through Delhi, Ayodhya, Banaras, Puri, Bengal, and up to Assam and Nepal. Accompanied by his faithful companion Bhai Mardana, a Muslim minstrel, he sang verses that awakened minds dulled by empty ritualism.

In Varanasi, he questioned the scholars and priests who had reduced spirituality to mechanical recitations. “Why chant mantras when compassion is forgotten?” he asked gently, reminding them that rituals without love are barren.

At Jagannath Puri, the priests invited him to witness the grand aarti (ritual offering of lamps). Instead, Nanak closed his eyes and sang his own aarti – not to an idol, but to the entire creation:

“The sky is the platter, the sun and moon are lamps;

The stars are pearls, the breeze is incense.”

It was a vision of the cosmos itself worshipping the Divine – a poetry that erased boundaries between temple and world.

Lesson from the First Udasi:

True worship lies not in ritual, but in wonder – in seeing the Divine in all creation.

The Second Udasi (1506-1513 CE):

The Message of the South

Guru Nanak’s second journey carried him deep into southern India – through Andhra, Tamil Nadu, Rameswaram, and across the sea to Sri Lanka (Ceylon).

In the South, he met kings, yogis, and saints. At Rameswaram, where Lord Rama was believed to have built a bridge to Lanka, Guru Nanak reminded devotees that no bridge is holier than one built by love.

In Sri Lanka, he met King Shivnabh, who, moved by Nanak’s wisdom, renounced his arrogance and embraced humility. The Guru taught that liberation was not found in renunciation, but in truthful living amidst the world.

Lesson from the Second Udasi

The path to God does not require withdrawal from life – it requires engagement with life through honesty, compassion, and humility.

The Third Udasi (1514-1518 CE):

The Call of the Mountains

The third journey led Guru Nanak northward – into the silence of the Himalayas, where he met ascetics, siddhas, and hermits who claimed spiritual superiority through seclusion.

At Mount Sumer, he encountered yogis who believed enlightenment could be achieved by abandoning worldly duties. Guru Nanak, clad simply and carrying no possessions, told them:

“The world is not to be renounced, but to be transformed through righteousness.”

He taught the Siddhas that true discipline is not in twisted limbs or breath control, but in controlling the mind and living truthfully amid temptation.

Lesson from the Third Udasi

The real ascetic is not one who flees the world, but one who lives in it with integrity and grace.

The Fourth Udasi (1519-1521 CE):

The Pilgrim of Oneness

Guru Nanak’s final great journey took him westward – across the Khyber Pass into Afghanistan, Persia, Mecca, and Baghdad. This was the most daring of all, for he entered lands bound by strict religious orthodoxy.

In Mecca, legend says, he was found sleeping with his feet pointing toward the Kaaba. When rebuked, he calmly replied, “Then turn my feet in the direction where God is not.” The astonished caretakers realized – the Divine is everywhere.

In Baghdad, he met spiritual leaders who, after initial skepticism, bowed to his universal message. His dialogue with Pir Dastgir and Bahlol Dana became famous – a conversation of light between souls.

Through this journey, Guru Nanak united East and West, Hindu and Muslim, saint and scholar – all through the gentle power of truth.

Lesson from the Fourth Udasi

God has no religion, no language, and no geography. To know the Divine, one must first know humanity.

The Pilgrim Returns:

Kartarpur and the Final Message

After two decades of wandering, Guru Nanak returned to Punjab and founded Kartarpur Sahib, the world’s first Sikh commune. There, he sowed the seeds of the Sikh way – the Three Pillars of Sikh Living: Naam Japna (Meditation on the Divine Name), Kirat Karna (Honest Living), Vand Chhakna (Sharing with Others).

It was as if the lessons from all four Udasis had crystallized into a living example – a community without discrimination, where men and women worked, prayed, and ate together as equals.

Kartarpur was not just a village – it was the world Guru Nanak had envisioned through his journeys: a world of Oneness, equality, and love.

The Enduring Footsteps

Guru Nanak’s travels covered over 30,000 miles – without armies, wealth, or scriptures. His companions were humility and song; his message, the eternal truth of unity.

Through forests, kingdoms, and deserts, he carried a lamp lit by love – challenging kings and comforting peasants, dissolving boundaries that still divide the world today.

His Udasis were not missionary expeditions; they were journeys of awakening – journeys that transformed humanity’s understanding of God and self.

Lessons from the Pilgrim of Peace

– Oneness of All: Divinity flows through all – beyond religion or race.

– Truthful Living: Spirituality is proven through conduct, not appearance.

– Equality: No one is high or low; all are equally divine.

– Compassion in Action: Service (seva) is the highest form of devotion.

– Fearless Inquiry: Questioning is not rebellion – it is the path to wisdom.

The Eternal Journey

More than five centuries have passed, yet Guru Nanak’s footsteps still echo across continents. Every Gurdwara, every Langar, every act of seva – carries forward the legacy of that Pilgrim of Peace who walked the world to remind us that “Ik Onkar” – There is One Eternal Reality.

The world he envisioned – without borders, without prejudice, without fear – remains the destination toward which humanity still walks.

Because the journey of Guru Nanak never truly ended.

It continues – in every heart that dares to see all beings as one. -

Breaking barriers: Guru Nanak’s feminist vision

In the dusty lanes of 15th-century Punjab, amid the murmurs of caste and the silence of subjugation, a boy named Nanak began asking questions that few dared to utter.

Why were some called pure and others untouchable?

Why were men deemed divine and women impure?

Why did rituals overshadow compassion?

These were not questions of rebellion – they were questions of realization.

By the time Guru Nanak Dev Ji (1469-1539) emerged as a spiritual luminary, he had already begun reshaping the moral geometry of his time. His message was simple but seismic: All are equal before the Divine.

And within that universal equality lay one of his most revolutionary truths – the elevation of women.

The Verse That Shattered Patriarchy

In the sacred hymn Asa di Var, Guru Nanak proclaimed words that would echo through centuries:

“So kyo manda aakhiye, jit jamme raajan?”

“How can she be called inferior, from whom kings are born?”

In one stroke, he dismantled generations of patriarchal prejudice. Women – often silenced by social and religious codes – were placed at the center of divine creation.

He declared that woman is not to be condemned but revered, for she is both life-giver and the reflection of the Infinite.

These words were not a poetic flourish – they were a theological revolution. At a time when religious texts excluded women from spiritual discourse, Guru Nanak’s verse became a manifesto for gender dignity.

A Revolution in Practice

Guru Nanak was not a philosopher of abstraction; he was a man of living truth. He did not merely preach equality – he practiced it.

He rejected the taboos that labeled women as impure due to menstruation or childbirth, calling such ideas ignorance of divine creation. He emphasized that both men and women carried the same divine light – Jyot.

He said:

“From woman, man is born; within woman, man is conceived;

to woman he is engaged and married.

Why call her bad? From her, kings are born.”

In his eyes, woman was not to be worshipped as goddess or reduced to servitude – she was coequal in the spiritual journey. The path to divine realization was open to all, regardless of gender.

Voices of Strength

Guru Nanak’s message empowered the women closest to him – and they, in turn, became beacons for generations.

Bebe Nanaki

His elder sister, Bebe Nanaki, was the first to recognize his divine calling. Her faith, support, and intuitive understanding of her brother’s spiritual light made her the first Sikh in history. She symbolizes intuitive devotion and feminine wisdom – the balance between love and discernment.

Mata Khivi – The Nurturing Reformer

The wife of Guru Angad Dev Ji, Mata Khivi, institutionalized one of Sikhism’s greatest contributions to humanity – the Langar, or community kitchen. Under her care, the Langar became a living embodiment of equality: men and women, rich and poor, sat together to share food without discrimination.

Her compassion and management were so revered that she is mentioned by name in the Guru Granth Sahib, an honor shared by very few women in religious scriptures.

Mai Bhago – The Warrior Saint

Centuries later, Guru Nanak’s message would inspire women like Mai Bhago, the fearless warrior who led forty deserters back into battle in the time of Guru Gobind Singh Ji. Her courage became the living proof that spiritual strength and physical valor were not male monopolies.

From nurturing souls to leading armies – Sikh women embodied the full spectrum of strength envisioned by Guru Nanak.

The Spiritual Feminism of Sikhism

What makes Guru Nanak’s vision unique is that his feminism was rooted in spirituality, not politics.

He did not demand social change as an act of rebellion – he unveiled spiritual truth as the natural foundation for social justice. If the soul is without gender, then discrimination against women is not merely unjust – it is untrue.

The Guru Granth Sahib, the living scripture of the Sikhs, reflects this balance beautifully. It uses both masculine and feminine imagery for the Divine. God is sometimes Pita (Father), sometimes Mata (Mother), and often neither, transcending all form and gender.

This oneness of being – Ik Onkar – is the spiritual essence of equality.

Institutional Equality: Sikh

Practices That Empower Women

Guru Nanak ensured that his vision did not remain confined to words. He institutionalized it within the Sikh community structure:

– Sangat (Congregation): Men and women sit together with no segregation, reinforcing spiritual unity.

– Pangat (Community Meal): Everyone, regardless of caste or gender, eats side by side.

– Kirtan and Seva: Women can perform hymns, read from the Guru Granth Sahib, lead prayers, and perform any religious duty – complete equality in spiritual service.

– Leadership: Sikh women have historically led Gurdwaras, schools, and humanitarian missions, carrying forward the Guru’s legacy in the modern age.

This wasn’t just progressive – it was centuries ahead of its time.

Modern Reflections: Women of the Guru’s Light

Today, Guru Nanak’s teachings continue to inspire Sikh women around the world – from the gurdwaras of Amritsar to the community kitchens of London, Vancouver, and Nairobi.

– In Education: Sikh women head universities, schools, and interfaith organizations, promoting literacy and equality.

– In Humanitarian Work: Groups like Khalsa Aid see women at the forefront of global relief, serving refugees, disaster victims, and the homeless.

– In Spiritual Leadership: Women now perform Kirtan at the Golden Temple and lead online Sangats, bringing the Guru’s wisdom to new generations.

Beyond Gender: The Eternal Message

Guru Nanak’s feminism was never confined to one gender; it was an invitation to transcend all binaries – male and female, high and low, rich and poor.

In his vision of Ik Onkar, all creation is part of one divine light. To discriminate against woman is to deny that divine unity.

He saw that true liberation comes not from asserting dominance, but from realizing oneness.

Thus, Guru Nanak’s message was not only feminist – it was humanist, universal, and timeless.

Legacy and Relevance Today

In an age when gender equality is still being debated and legislated, Guru Nanak’s message feels both ancient and astonishingly modern. He didn’t need to coin slogans or lead protests – he redefined consciousness itself.

For him, the measure of civilization was not power or conquest, but how a society treated its women.

His voice, echoing through the Guru Granth Sahib, still calls humanity to remember that spirituality is meaningless without equality.

“There is One God in all; there is no high or low.

Whoever realizes this truth, finds peace.” -

Equality in every grain: The legacy of langar

In a world that still grapples with hunger, inequality, and division, the simple act of sharing a meal can become a spiritual revolution. Over five hundred years ago, Guru Nanak Dev Ji, the founder of Sikhism, envisioned such a revolution – one that would begin not in palaces or temples, but in a humble kitchen. His idea was Langar, a free community kitchen that fed anyone and everyone, without discrimination.

Today, from the corridors of the Golden Temple in Amritsar to makeshift tents in disaster zones, from city streets to refugee camps, Langar continues to serve millions of meals every single day – a living embodiment of equality in action.

The Origins: A Meal That

Challenged Caste and Creed

To understand the Langar, one must return to the 15th century – a time when India was divided by rigid caste hierarchies and religious divisions. People were categorized not by their humanity, but by birth, occupation, and belief. The privileged ate separately, while the marginalized often went hungry.

Amid this injustice, Guru Nanak Dev Ji (1469-1539) emerged as a voice of divine compassion and moral courage. From a young age, he questioned meaningless rituals and hypocrisy in religion. His defining moment came during his youth, when his father, Mehta Kalu, gave him 20 rupees to start a business – a test of his responsibility.

Instead of seeking profit, Nanak spent the money feeding a group of hungry ascetics. When reprimanded, he calmly replied,

“This was Sacha Sauda – the True Trade.”

That act – choosing compassion over commerce – marked the seed of Langar. Years later, as Guru Nanak established the first Sikh commune at Kartarpur Sahib, he institutionalized the Langar as a permanent part of Sikh practice. Everyone, regardless of caste, gender, or religion, would sit together and eat the same food, symbolizing oneness before God.

Langar: A Radical Act of Equality

Langar was far more than charity; it was a spiritual declaration. In a society where upper castes refused to eat with “lower-born” individuals, Guru Nanak’s Langar erased all such distinctions. The concept of sitting together in a pangat (row) to share a simple meal was an act of rebellion against social inequality and a profound expression of humility.

Mata Khivi: The First Lady of Langar

An often-overlooked yet central figure in the Langar tradition is Mata Khivi Ji, wife of Guru Angad Dev Ji (the second Sikh Guru). She is lovingly remembered in the Guru Granth Sahib for her graciousness and dedication in managing the Langar at Khadoor Sahib.

She organized, expanded, and systemized the community kitchen – ensuring that every visitor received warm food, kindness, and respect. Under her care, Langar became an institution of dignity, where both men and women served equally. Mata Khivi’s example established seva (selfless service) as the heartbeat of Sikh communal life.

Langar Through the Centuries

The Gurus who followed Guru Nanak strengthened the Langar tradition. Guru Amar Das Ji made participation in Langar a precondition for audience with him – even emperors had to sit in the pangat before meeting the Guru. This simple act symbolized humility and the breaking down of hierarchy.

By the time of Guru Arjan Dev Ji, Langar was a defining identity of the Sikh community. The tradition became inseparable from the Gurdwara (Sikh temple), ensuring that no one would leave hungry from the house of God.

When the magnificent Golden Temple (Harmandir Sahib) was constructed, the Langar became its soul. To this day, the Golden Temple serves over 100,000 free meals daily, using nearly 50 quintals of wheat flour, 18 quintals of dal, and 12 quintals of rice – all prepared and served by volunteers.

The Spirit of Seva: Service Without Self

The essence of Langar lies not only in the food but in the spirit of seva. Every task – from peeling onions to washing dishes – is done as a spiritual offering, without expectation of reward or recognition.

Volunteers, known as sevadars, come from all walks of life: farmers, doctors, homemakers, students, even tourists. All cover their heads, remove their shoes, and work shoulder-to-shoulder in humility. In the eyes of the Guru, all are equal. There is no hierarchy in Langar – only harmony.

Global Reach: Langar Without Borders

What began in a small village on the banks of the River Ravi has now become a global humanitarian movement. Wherever Sikhs have settled, they have carried the tradition of Langar with them – to Canada, the UK, the US, Australia, Kenya, and beyond.

During times of crisis, Langar becomes a lifeline.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Gurdwaras across the world delivered meals to hospitals, stranded workers, and the homeless.

Khalsa Aid, inspired by Guru Nanak’s teachings, set up mobile kitchens in war-torn regions like Iraq, Syria, and Ukraine.

In London, the “Midnight Langar” at Trafalgar Square feeds the homeless every weekend.

In Melbourne and Toronto, Sikh youth organizations distribute food in public parks and train stations.

Each meal served is a continuation of Guru Nanak’s vision – spirituality through action, compassion beyond boundaries.

Why Langar Matters Today

In an age defined by social media excess, food waste, and growing inequality, the Langar stands as a beacon of simplicity and sustainability. It teaches that the greatest form of worship is not chanting prayers in isolation, but feeding a hungry soul with love.

It also challenges modern notions of charity. Langar is not about giver and receiver – it’s about shared humanity. Both the one who serves and the one who eats are spiritually nourished.

Even in 2025, the relevance of Guru Nanak’s Langar is profound:

– It fosters interfaith harmony by welcoming all.

– It combats hunger and food insecurity in practical ways.

– It teaches environmental responsibility through minimal waste and community cooking.

– And it inspires volunteerism and humility in a world driven by self-interest.

A Meal of the Soul

Langar is more than food – it is faith served on a plate. Each roti rolled, each dal stirred, and each thali washed carries the message of Ik Onkar – One Universal Creator. It dissolves the illusion of separateness and reminds us that divinity dwells in every being.

As Guru Nanak taught:

“Recognize the Lord’s light within all, and do not consider social class or status.

There are no strangers – no one is high or low.”

The Eternal Table of Humanity

Five centuries later, the aroma of Langar still rises from Gurdwaras across continents – a fragrance of equality, humility, and love. Beneath that fragrance lies the timeless wisdom of Guru Nanak Dev Ji: that spirituality is not an escape from the world but a transformation of it.

In every grain cooked and shared in Langar lives the heartbeat of humanity. In every hand that serves and every hand that receives, God is found. -

The river that changed everything

In the tranquil town of Sultanpur Lodhi, where the Kali Bein flows like a silver thread through the Punjab . Guru Nanak, then a humble storekeeper in the service of the local governor, had already begun to stanplains, a miracle unfolded that changed the spiritual landscape of India forever. The year was around 1499d apart from his contemporaries – his heart restless, his spirit drawn to the eternal questions of existence.