A Wound That Refuses to Heal: On the 41st Anniversary of Operation Blue Star

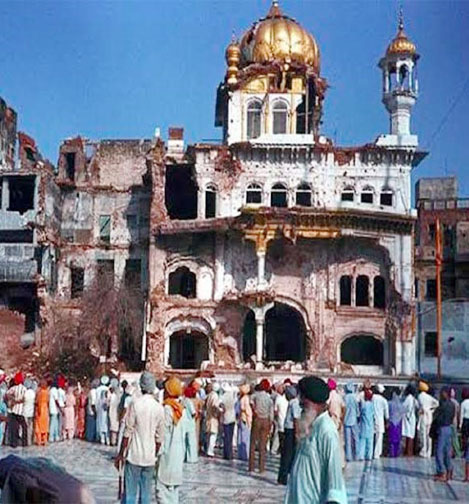

In the summer of 1984, a tragic and defining chapter unfolded in Indian history—Operation Blue Star, a military action ordered by the Indian government under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, to flush out Sikh militants, including […]