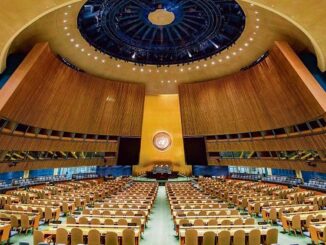

Need to review UN Charter to reflect change

The first step towards strengthening the multilateral system must, therefore, begin with removing the contradictions within the UN Charter on decision-making “As the UN prepares to mark its 80th anniversary in September 2025, it is […]