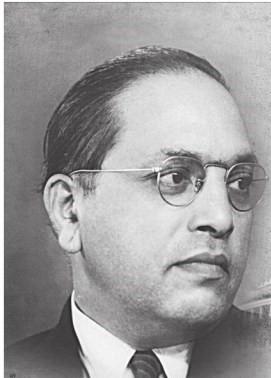

India at 77: The Republic’s Journey, Its Promises, and Its Tests

On January 26, 2026, India will mark the 77th anniversary of its Republic—a moment not merely of celebration, but of reflection. Republic Day is not about pomp alone; it is a reminder of a constitutional […]