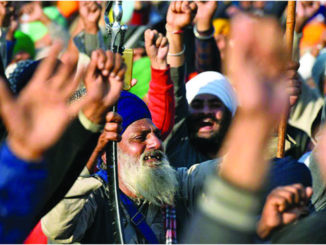

Sanyukta Kisan Morcha suspends protest aftergovt agrees to most of their demands

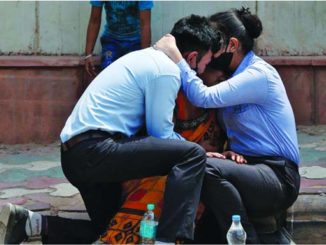

Experts call agitation ‘enriching of democracy’, but also term victory as one ‘forced due to political compulsions’ NEW DELHI (TIP): As the leaders of the Samyukta Kisan Morcha on Thursday, December 9, formally announced the […]