Perspective

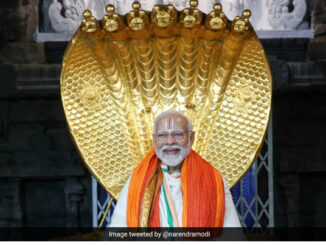

Saints, Sadhvis, and the State: How Political Hinduism is Rewriting India’s Democracy

The danger is no longer in the future—it’s already here. As rituals replace reason, and holy men replace elected representatives in moral authority, India risks becoming a de facto Hindu nation in all but name. […]