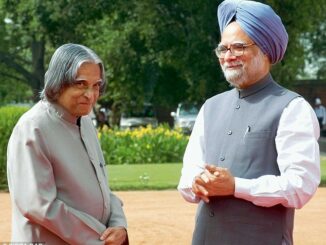

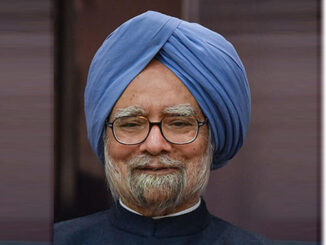

2 sites shortlisted for Dr. Manmohan Singh Memorial

NEW DELHI (TIP): The government has shortlisted two locations for allotment of land to build a memorial to late Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. Union Urban Affairs Minister Manohar Lal Khattar on Thursday said the two […]