History records many warriors, reformers, and martyrs. Yet there is no parallel in world history to the scale and depth of sacrifice made by Guru Gobind Singh Ji, the tenth Sikh Guru, in defense of human dignity, freedom of faith, and basic human rights. In a life cut short at 48, Guru Gobind Singh did not merely resist tyranny—he redefined the moral duty of resistance itself.

Seventeenth-century India was a land under strain. The Mughal Empire, particularly during the reign of Aurangzeb, had increasingly embraced religious orthodoxy enforced by state power. Forced conversions, destruction of temples, discriminatory taxation, and brutal suppression of dissent had become instruments of governance. It was against this backdrop that Guru Gobind Singh emerged—not as a rebel seeking power, but as a moral leader challenging injustice at its very roots.

The foundations of this struggle were laid when Guru Gobind Singh was still a child. At the age of eight or nine, he witnessed one of the most defining moments in Indian history. Kashmiri Pandits, facing forcible conversion, sought protection from his father, Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji. It was the young Gobind Rai who urged his father to stand firm, even at the cost of his life. Guru Tegh Bahadur’s martyrdom in 1675 was an unprecedented act, a spiritual leader laying down his life not for his own faith, but for the right of another community to practice theirs. It marked a watershed moment in the evolution of religious freedom in India.

This early exposure to supreme sacrifice shaped Guru Gobind Singh’s philosophy. For him, spirituality was inseparable from social responsibility. Faith that did not defend the oppressed was hollow; devotion that ignored injustice was incomplete. These beliefs would later find their most powerful expression in the creation of the Khalsa in 1699.

The establishment of the Khalsa at Anandpur Sahib was not merely a religious event; it was a social revolution. By initiating ordinary men into a disciplined brotherhood of saint-soldiers, Guru Gobind Singh dismantled centuries of caste hierarchy, fear, and submission. The Khalsa was founded to ensure that no individual would remain defenseless in the face of tyranny. It fused moral purity with martial courage, creating a model of resistance grounded in ethics rather than vengeance.

Predictably, such an egalitarian force alarmed both the Mughal authorities and local hill rulers. Guru Gobind Singh spent much of his life in a state of siege—physically, politically, and spiritually. Battles were frequent, resources limited, and betrayals painful. Yet he never deviated from his core principles. His struggle was not against any religion, but against oppression and injustice, regardless of their source.

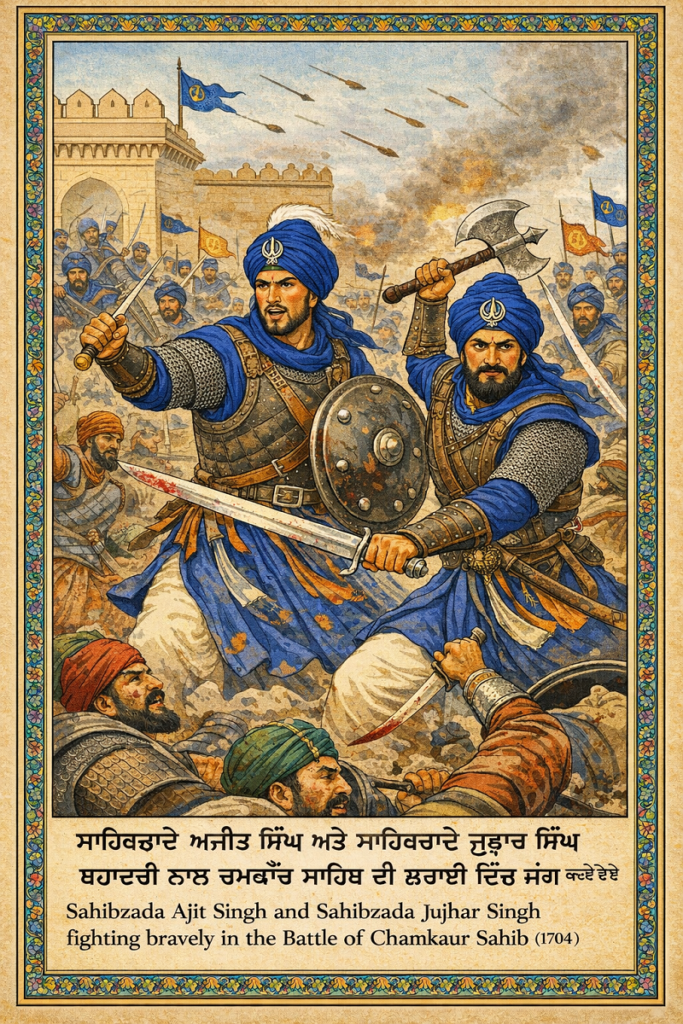

The most tragic and defining chapter of his life unfolded in December 1704, during the battle of Chamkaur Sahib. Vastly outnumbered by Mughal forces, Guru Gobind Singh took a decision that continues to challenge human comprehension. He sent his two elder sons—Sahibzada Ajit Singh and Sahibzada Jujhar Singh, both in their teens—into battle. They fought with extraordinary bravery and fell as martyrs. Their deaths were not acts of youthful recklessness, but conscious offerings to the cause of freedom and dignity.

Even this was not the end of his suffering. Shortly thereafter, his younger sons—nine-year-old Sahibzada Zorawar Singh and seven-year-old Sahibzada Fateh Singh—were captured at Sirhind. Offered life in exchange for conversion to Islam, the children refused. They were bricked alive for their faith. Few episodes in history expose the cruelty of religious coercion as starkly as this. Fewer still reveal the power of moral upbringing so vividly—children choosing death over the surrender of conscience.

What distinguishes Guru Gobind Singh from many historical figures is not merely the magnitude of his loss, but his response to it. Despite losing all four sons, he neither retreated into despair nor sought revenge. Instead, he reaffirmed his faith in divine justice and continued to inspire resistance rooted in righteousness. His writings reflect resilience, courage, and an unshakeable belief that tyranny, however powerful, is ultimately transient.

Guru Gobind Singh’s philosophy was strikingly modern. Long before the language of “human rights” entered political discourse, he articulated and defended its core principles: equality of all human beings, freedom of belief, resistance to injustice, and the dignity of the individual. His life demonstrated that rights are not granted by rulers; they are claimed and defended by people of conscience.

There is a poignant symbolism in the calendar itself. In 2025, the martyrdom of the four Sahibzadas is commemorated from December 22 when the older Sahibzadas- Baba Ajit Singh and Baba Jujhar Singh were martyred in the Battle of Chamkaur Sahib, on to December 27, when the younger Sahibzadas- Baba Zorawar Singh and Baba Fateh Singh-were bricked alive, while Guru Gobind Singh’s birth anniversary falls on December 27. This period, often described as a martyrdom week, encapsulates the essence of his life—where birth and sacrifice, celebration and sorrow, are inseparably intertwined. It is a reminder that the freedoms enjoyed today are rooted in endured yesterday.

In an era when authoritarianism, religious intolerance, and erosion of civil liberties continue to challenge societies worldwide, Guru Gobind Singh’s life carries urgent relevance. He teaches that neutrality in the face of injustice is moral failure, that faith must empower ethical action, and that true leadership demands personal sacrifice.

As we observe the Martyrdom Week, commemorating the extraordinary bravery, courage, and steadfastness of the Sahibzadas, and celebrate the Prakash Divas (birth anniversary) of Guru Gobind Singh Ji, let this sacred period be more than remembrance. Let it be a renewed pledge. A pledge to walk in their footsteps, to resist injustice in all its forms, and to protect the fundamental human rights to freedom and dignity of every individual—regardless of race, color, creed, or belief. In honoring Guru Gobind Singh and his sons, we reaffirm not only a chapter of history, but a timeless moral responsibility that remains as urgent today as it was more than three centuries ago.

Be the first to comment