India’s freedom struggle: From first invasion to midnight of Independence

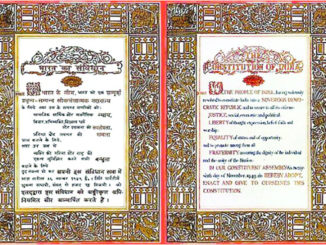

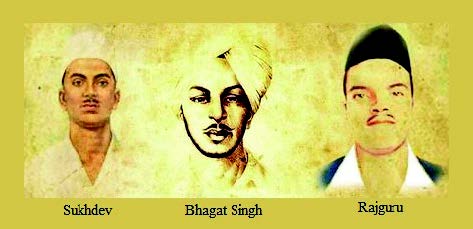

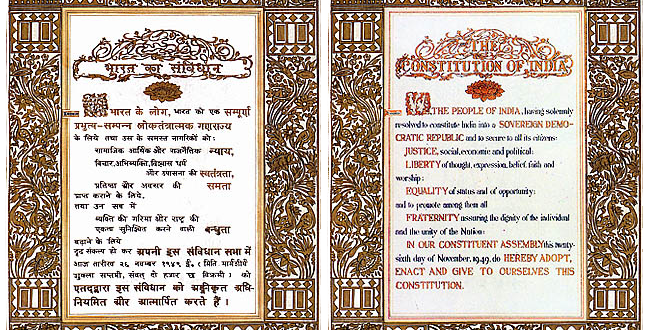

India’s journey to freedom was neither swift nor simple-it was a centuries-long saga of resilience, rebellion, and renaissance. While the climax arrived on 15 August 1947, the struggle had its roots in the earliest invasions […]