The birth anniversary of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, is celebrated as Children’s Day on November 14. A champion of children’s education and rights, Nehru was honored posthumously in 1964, when the government passed a resolution designating this day as Children’s Day. This act aimed to commemorate his significant contribution to the welfare of children in society.

Every year, November 14 in India bursts into color, laughter, and innocence. Schools resound with giggles instead of lessons, teachers turn performers, and playgrounds become stages of joy. This day – Children’s Day, or Bal Diwas – celebrates the purest form of humanity: childhood.

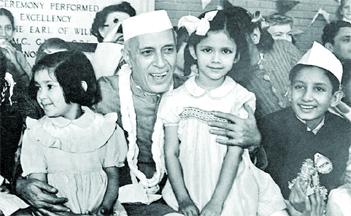

But beyond the balloons, sweets, and fun, lies a deeper tribute – to Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, whose birthday marks this special occasion and whose affection for children shaped the very idea of post-independence India’s future.

The Man Behind the Day

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru was born on November 14, 1889, in Allahabad, into a family deeply rooted in India’s freedom struggle. A visionary leader, thinker, and statesman, Nehru played a central role in the country’s journey to independence and its early years as a modern democratic republic.

Yet, amid his intellectual brilliance and political leadership, there was another side to him – one filled with tenderness and idealism. He loved spending time with children, often calling them the true wealth of the nation. Children, in turn, fondly called him “Chacha Nehru”, an affectionate name that reflected both his warmth and humility.

For Nehru, children symbolized hope, potential, and purity – the untainted spirit that could build a better, progressive India. He often said,

“The children of today will make the India of tomorrow. The way we bring them up will determine the future of our country.”

Following his death in 1964, his birthday began to be celebrated as Children’s Day, a day dedicated to honoring his love for the young and his dream of nurturing them as the builders of a new India.

From Leader to Chacha Nehru

Nehru’s fondness for children was not merely sentimental; it was deeply philosophical. He believed that childhood must be protected – not just with affection, but through education, equality, and opportunity.

His government’s focus on establishing educational institutions like IITs, AIIMS, and agricultural universities reflected this commitment to shaping young minds.

He saw in every child a potential scientist, artist, thinker, and dreamer – waiting to bloom. For him, nurturing children wasn’t charity; it was nation-building. That belief remains the soul of Children’s Day in India today.

How India Celebrates Children’s Day

Across the country, Children’s Day is celebrated with immense enthusiasm and creativity. Schools, NGOs, and communities organize special programs to honor the joy of childhood:

– Schools turn festive, with teachers organizing cultural shows, skits, magic performances, and games for their students.

– Competitions in art, poetry, storytelling, and sports encourage creativity and self-expression.

– Educational campaigns and exhibitions highlight the importance of child rights, health, and education.

– Children from underprivileged backgrounds are often invited to share the celebrations, reinforcing the spirit of equality and inclusion.

In many places, gifts, sweets, and books are distributed, not as indulgence but as gestures of care – echoing Chacha Nehru’s belief that love and knowledge are the two greatest gifts we can give to children.

The Universal Message of Childhood

While Children’s Day in India coincides with Nehru’s birthday, the message it carries transcends boundaries. It reminds us that every child – regardless of background or circumstance – deserves love, dignity, and opportunity.

In a world increasingly driven by competition and technology, the day serves as a reminder to preserve the innocence of childhood, to allow children to explore, question, and grow without fear. It calls upon parents, educators, and society to ensure that no child is deprived of education, safety, or a nurturing environment.

As Nehru once wrote in his book Letters from a Father to His Daughter,

“Life is like a book, and those who do not travel or learn read only a page.”

His words continue to inspire the idea that education – both formal and experiential – is the greatest gift we can offer our children.

Children’s Day in the Modern Context

In today’s fast-paced world, where screens have replaced playgrounds and pressure often shadows playtime, the essence of Children’s Day holds renewed importance.

It is not merely a celebration but a reminder to safeguard childhood – to let children be curious, joyful, and imaginative.

Organizations across India use this day to raise awareness about child rights, mental health, and the importance of emotional development. From campaigns promoting child literacy to drives against child labor, the day has evolved from a festive occasion into a social mission.

Legacy of Love and Learning

Pandit Nehru’s deep empathy for children stemmed from his belief that the future of any nation depends on how it treats its young. His dream was of a society that respected freedom of thought, scientific curiosity, and compassion – values that must be instilled early in life. He envisioned schools not as rigid institutions but as gardens where young minds could grow freely, guided by teachers who understood that every child’s curiosity is sacred.

In remembering him each year, we are reminded not just of his affection for children, but of his vision – a world where every child is educated, empowered, and loved.

A Day to Cherish Innocence

Children’s Day is more than a date on the calendar – it is a celebration of laughter, learning, and limitless dreams. It’s a call to every adult to see the world once again through a child’s eyes – with wonder, empathy, and hope.

As schools across India echo with the songs of young voices, and as flowers are placed at Nehru’s samadhi at Shantivan, the message remains timeless:

To honor children is to honor the future itself.

Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of independent India (1947–64), was born on November 14, 1889, in Allahabad, India. He established parliamentary government and became noted for his neutralist (nonaligned) policies in foreign affairs. He was also one of the principal leaders of the Indian Independence Movement during the 1930s and ’40s.

Early years

Nehru was born to a family of Kashmiri Brahmans, noted for their administrative aptitude and scholarship, who had migrated to Delhi early in the 18th century.

He was a son of Motilal Nehru, a renowned lawyer and leader of the Indian independence movement, who became one of Mohandas (Mahatma) Gandhi’s prominent associates. Jawaharlal was the eldest of four children, two of whom were girls. A sister, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, later became the first woman president of the United Nations General Assembly.

Until the age of 16, Nehru was educated at home by a series of English governesses and tutors. Only one of those—a part-Irish, part-Belgian theosophist, Ferdinand Brooks—appears to have made any impression on him. Jawaharlal also had a venerable Indian tutor who taught him Hindi and Sanskrit. In 1905 he went to Harrow, a leading English school, where he stayed for two years. Nehru’s academic career was in no way outstanding. From Harrow he went to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he spent three years earning an honours degree in natural science. On leaving Cambridge he qualified as a barrister after two years at the Inner Temple, London, where in his own words he passed his examinations “with neither glory nor ignominy.”

The seven years Nehru spent in England left him in a hazy half-world, at home neither in England nor in India. Some years later he wrote, “I have become a queer mixture of East and West, out of place everywhere, at home nowhere.” He went back to India to discover India. The contending pulls and pressures that his experience abroad were to exert on his personality were never completely resolved.

Four years after his return to India, in March 1916, Nehru married Kamala Kaul, who also came from a Kashmiri family that had settled in Delhi. Their only child, Indira Priyadarshini, was born in 1917; she would later (under her married name of Indira Gandhi) also serve (1966–77 and 1980–84) as prime minister of India. In addition, Indira’s son Rajiv Gandhi succeeded his mother as prime minister (1984–89).

Political apprenticeship

On his return to India, Nehru at first had tried to settle down as a lawyer. Unlike his father, however, he had only a desultory interest in his profession and did not relish either the practice of law or the company of lawyers. For that time he might be described, like many of his generation, as an instinctive nationalist who yearned for his country’s freedom, but, like most of his contemporaries, he had not formulated any precise ideas on how it could be achieved.

Nehru’s close association with the Congress Party dates from 1919 in the immediate aftermath of World War I. That period saw an early wave of nationalist activity and governmental repression, which culminated in the Massacre of Amritsar in April 1919; according to an official report, 379 persons were killed (though other estimates were considerably higher), and at least 1,200 were wounded when the local British military commander ordered his troops to fire on a crowd of unarmed Indians assembled in an almost completely enclosed space in the city.

When, late in 1921, the prominent leaders and workers of the Congress Party were outlawed in some provinces, Nehru went to prison for the first time. Over the next 24 years he was to serve another eight periods of detention, the last and longest ending in June 1945, after an imprisonment of almost three years. In all, Nehru spent more than nine years in jail. Characteristically, he described his terms of incarceration as normal interludes in a life of abnormal political activity.

His political apprenticeship with the Congress Party lasted from 1919 to 1929. In 1923 he became general secretary of the party for two years, and he did so again in 1927 for another two years. His interests and duties took him on journeys over wide areas of India, particularly in his native United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh state), where his first exposure to the overwhelming poverty and degradation of the peasantry had a profound influence on his basic ideas for solving those vital problems. Though vaguely inclined toward socialism, Nehru’s radicalism had set in no definite mold. The watershed in his political and economic thinking was his tour of Europe and the Soviet Union during 1926–27. Nehru’s real interest in Marxism and his socialist pattern of thought stemmed from that tour, even though it did not appreciably increase his knowledge of communist theory and practice. His subsequent sojourns in prison enabled him to study Marxism in more depth. Interested in its ideas but repelled by some of its methods—such as the regimentation and the heresy hunts of the communists—he could never bring himself to accept Karl Marx’s writings as revealed scripture. Yet from then on, the yardstick of his economic thinking remained Marxist, adjusted, where necessary, to Indian conditions.

Struggle for Indian independence

After the Lahore session of 1929, Nehru emerged as the leader of the country’s intellectuals and youth. Gandhi had shrewdly elevated him to the presidency of the Congress Party over the heads of some of his seniors, hoping that Nehru would draw India’s youth—who at that time were gravitating toward extreme leftist causes—into the mainstream of the Congress movement. Gandhi also correctly calculated that, with added responsibility, Nehru himself would be inclined to keep to the middle way.

After his father’s death in 1931, Nehru moved into the inner councils of the Congress Party and became closer to Gandhi. Although Gandhi did not officially designate Nehru his political heir until 1942, the Indian populace as early as the mid-1930s saw in Nehru the natural successor to Gandhi. The Gandhi-Irwin Pact of March 1931, signed between Gandhi and the British viceroy, Lord Irwin (later Lord Halifax), signalized a truce between the two principal protagonists in India. It climaxed one of Gandhi’s more-effective civil disobedience movements, launched the year before as the Salt March, in the course of which Nehru had been arrested. When the elections following the introduction of provincial autonomy brought the Congress Party to power in a majority of the provinces, Nehru was faced with a dilemma. The Muslim League under Mohammed Ali Jinnah (who was to become the creator of Pakistan) had fared badly at the polls. Congress, therefore, unwisely rejected Jinnah’s plea for the formation of coalition Congress–Muslim League governments in some of the provinces, a decision that Nehru had supported. The subsequent clash between the Congress and the Muslim League hardened into a conflict between Hindus and Muslims that was ultimately to lead to the partition of India and the creation of Pakistan.

The Architect of Modern India

Jawaharlal Nehru was the first Prime Minister of independent India. One of the most prominent leaders of India’s Independent Movement, Pandit Nehru is known as the architect of modern India.

Pandit Nehru or Chacha Nehru as he was affectionately called was a nationalist leader, social democrat, author, and humanist.

Nehru was known for his vision, administrative aptitude, and scholastic prowess.

It was Jawaharlal Nehru who set out to realise the dream of a strong and resurgent India. He steered the nation to the path of recovery and modernisation. Nehru had neither the resources or the experience to administer the country. Yet, it was with his patriotism, dedication and commitment that he translated the values of the Congress into the Constitution of India.

It was Nehru who proposed the idea of fundamental rights and socio-economic equality irrespective of caste, creed, religion and gender. He invariably advocated the abolition of untouchability, right against exploitation, religious tolerance and secularism. He championed the idea of freedom of expression, right to form association, and was of the firm belief that statehood would ensure social and economic justice for labour and peasantry and give voting rights to all adult citizens. These propositions phrased by Jawaharlal Nehru made him the darling of India.

Here are some big decisions that nicknamed him an architect of modern India:

Establishing institutions of excellence

It was Nehru who provided the scientific base for India’s space supremacy and engineering excellence. With the establishment of Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) and universities, it was Nehru who put India on the path of development. Also, the foundation of the dual tack nuclear programme helped India achieve its nuclear enabled status. He also potentially set the pitch for industries, factories and the manufacturing sector paving the way for a journey of sovereign India.

Be the first to comment