Science & Technology

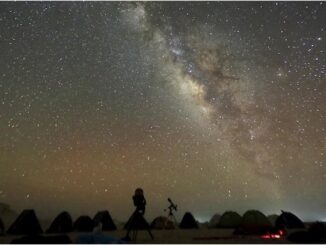

Scientists release the most accurate map of all the matter in universe

We are all made of matter. This matter was first thrown outwards in the moments after the Big Bang when our universe came into existence. Over centuries it all packed together to form planets and […]