Indian Americans

Punjabi diaspora in the US to make documentary on Ghadar movement and its founder Sohan Singh Bhakna

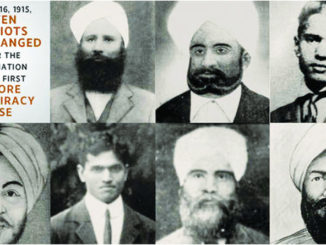

NORTH PORTLAND (TIP): A section of the Punjabi diaspora in the US’s North Portland has announced to film a documentary on the Ghadar movement and its founder Sohan Singh Bhakna, whose image will also appear […]