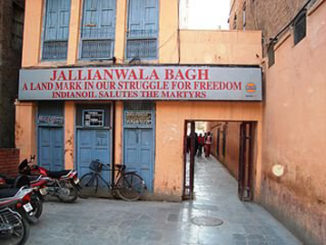

Jallianwala Bagh, a conspiracy or a planned massacre?

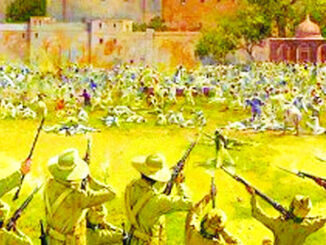

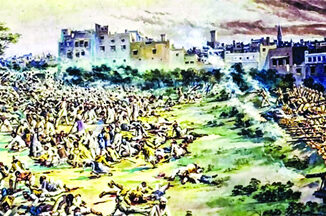

Is it time for the British Empire to apologize for the worst massacre reported in recent times? The Jallianwala Bagh massacre, also known as the Amritsar massacre, took place on 13 April 1919. A large […]