The History of India’s Republic Day

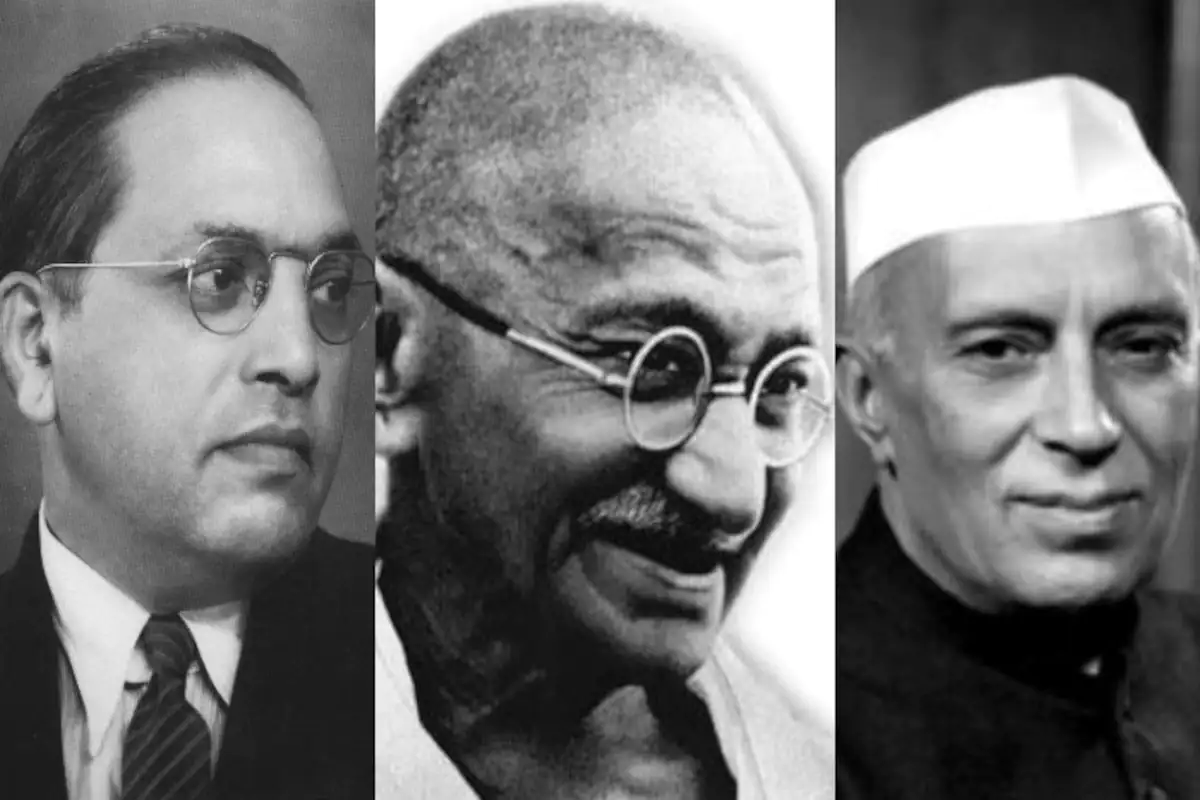

India’s Republic Day, celebrated annually on January 26, holds profound historical and cultural significance. This day marks the moment in 1950 when the Constitution of India came into effect, replacing the colonial Government of India […]