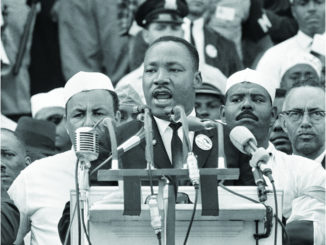

Martin Luther King Jr.: When History Became a Life, and a Life Became History

In three days, America will once again commemorate Martin Luther King Jr.,a man whose life became inseparable from the moral history of the United States. King is remembered not merely as a charismatic speaker or […]