Martyrdom day of Guru Arjan Dev ji

Each year, millions of Sikhs around the world solemnly commemorate the Martyrdom Day of Guru Arjan Dev Ji, the fifth Guru of Sikhism and the first Sikh martyr, whose death in 1606 CE became a […]

Each year, millions of Sikhs around the world solemnly commemorate the Martyrdom Day of Guru Arjan Dev Ji, the fifth Guru of Sikhism and the first Sikh martyr, whose death in 1606 CE became a […]

Bhagat Singh, Azad, Rajguru, Sukhdev, Ram Prasad Bismil, Gandhi, and Bose are few names that are synonymous with our struggle for freedom from the British. We owe our freedom to them. But apart from these […]

A nation is known by its people. The strength of a nation is known by its heroes. The character of a nation is known by its martyrs. With the Martyrs Day (March 23), commemorating the […]

The Komagata Maru incident involved the Japanese steamship Komagata Maru, on which a group of people from British India attempted to immigrate to Canada in April 1914, but most were denied entry and forced to […]

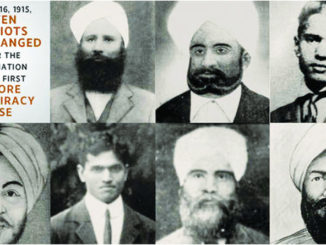

On November 16, 1915, seven patriots were hanged after the culmination of the first Lahore Conspiracy Case. These hangings, however, did not deter the Ghadarites from waging a war against the British. These included Bakshish […]

© The Indian Panorama