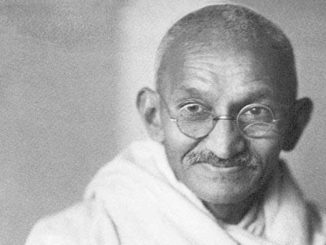

Remembering Mahatma Gandhi on his death anniversary

Martyrs’ Day is observed on January 30 to commemorate the death of Mahatma Gandhi, who was assassinated on the same day in 1948 Born Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, he is widely regarded as ‘Bapu’, or ‘Father […]