The ‘Donroe doctrine’, a broken international order

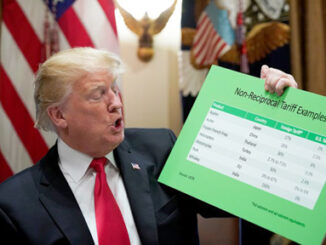

It is a mixed bag as far as the global outlook for 2026 is concerned, marked by an updated version of the U.S.’s ‘shock and awe’ tactics The new year began with a stark reminder […]

It is a mixed bag as far as the global outlook for 2026 is concerned, marked by an updated version of the U.S.’s ‘shock and awe’ tactics The new year began with a stark reminder […]

India cannot blame Western xenophobia while succumbing to it at home “Normally, domestic and foreign policies of countries are inter-related. The Trump administration demonstrates that by aligning its foreign policy with its MAGA supremacism. The […]

The three great powers understand that the world is no longer organized around a single center of authority As 2025 draws to a close, a highlight is that the United States has undertaken its largest […]

US-India relations have sunk to a new low, with the Cold War era distrust returning “As for the NSS, three things have so far been clarified. First, that Trump would like to, as it were, […]

With the Trump Administration’s National Security Strategy making it clear that American support to Europe is now faint, it remains to be seen how Europe responds Hope is not a strategy. For most of this […]

© The Indian Panorama