- Jay Mandal

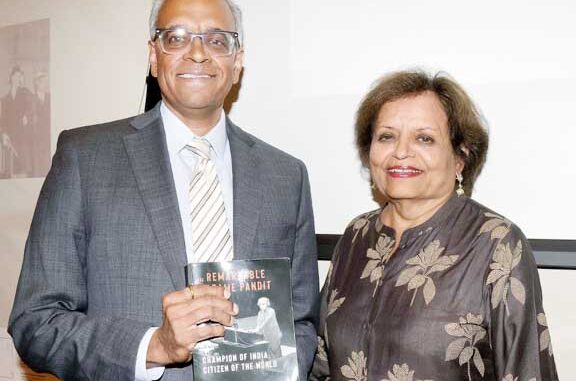

MANHATTAN, NY (TIP): Manu Bhagavan, the Hunter College professor and historian whose new biography, The Remarkable Madame Pandit: Champion of India, Citizen of the World, has drawn attention for its archival depth, appeared at Roosevelt House on the evening of September 16 for a moderated conversation with Vishakha Desai, President Emerita of the Asia Society. The program, hosted by the Roosevelt House Human Rights Program, brought together students, scholars, and New York’s South Asian community for a discussion of Pandit’s life and legacy, followed by a reception and book signing.

Bhagavan framed Pandit’s life as a bridge between Indian nationalism and mid-20th-century internationalism, emphasizing her early role in the independence movement, her service in India’s early cabinets, and her pioneering diplomatic career that culminated in her election as President of the UN General Assembly. The event description and publisher materials highlight Bhagavan’s use of international archives to complicate familiar narratives about Pandit — portraying her not simply as a first or a symbol, but as a sophisticated practitioner of public diplomacy who engaged major institutions and leaders across the globe. Desai steered the conversation toward two recurring themes: the gendered obstacles Pandit faced while operating in predominantly male institutions, and the tension between her global commitments and domestic political currents in India. According to the event brief and the moderator’s professional interests, Desai probed how Pandit negotiated authority and visibility — how she used family connections and political networks while also crafting an independent international voice. These topics, visible in the event synopsis and promotional text, animated much of the discussion.

Bhagavan illustrated his points with archival anecdotes and interpretive reframing (as summarized in promotional material): instances of Pandit’s decisive interventions at the United Nations, episodes that reveal her readiness to confront colonial and authoritarian power, and episodes of political fallout at home. While the program listing does not publish direct quotes, social posts from the day indicate a lively exchange and a full house, suggesting the material resonated strongly with the audience.

During the conversation, Bhagavan also explained how Madame Pandit spoke out against her niece, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, for imposing the national Emergency in 1975 and jailing opposition political leaders — a rare act of defiance within the Nehru-Gandhi family that underscored Pandit’s independence of judgment and commitment to democratic values.

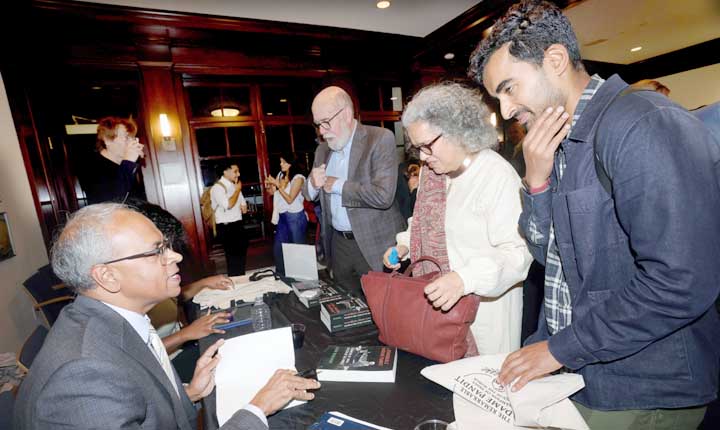

Audience reaction after the talk was enthusiastic. Social media posts and short video clips from the event show a standing-room crowd and a well-attended reception and signing immediately after the conversation, evidence that the book launch drew sustained interest from both academic and public audiences in New York.

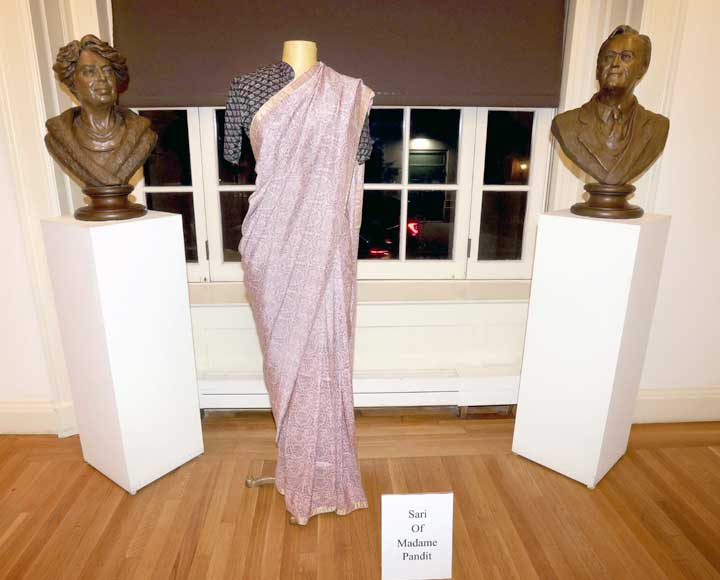

The highlight of the evening was the presence of Ms Gita Sahgal, Madame Pandit’s granddaughter (her daughter’s daughter), who also spoke briefly at the event. Adding to the sense of history, the program featured a display of the original sari that Madame Pandit famously wore on significant public occasions.

Bhagavan’s biography arrives as scholars and policy practitioners revisit mid-20th-century diplomacy and the role of women in shaping international institutions. The Roosevelt House conversation positioned Pandit as relevant to contemporary debates about gender and diplomacy, postcolonial leadership, and the moral stakes of international engagement, themes that the author and moderator highlighted as central to Pandit’s continuing relevance.

Be the first to comment