Perspective

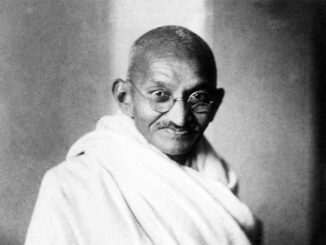

A betrayal of the very idea of the Mahatma

The principles Gandhiji stood for represent an ideal that is being weakened every day by those in power who are pushing their agenda of bigotry “The contradiction is mirrored in the attitude of the Hindutva-inspired […]