Featured

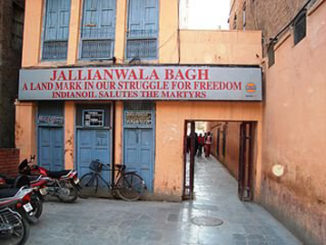

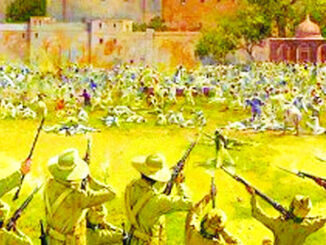

Bloodbath on Vaisakhi: The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre

April 13, 1919, marked a turning point in the Indian freedom struggle. It was Vaisakhi that day, a harvest festival popular in Punjab and parts of north India. Residents of Amritsar decided to assemble at […]