Sacrifices – Endurance in the face of tragedy

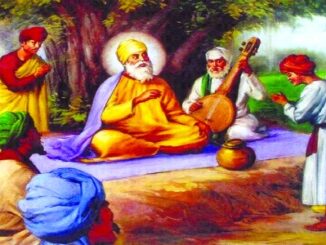

Guru Gobind Singh Ji, the tenth Sikh Guru, stands as a timeless symbol of courage, resilience, and unwavering faith. While celebrated for his spiritual guidance, poetic genius, and martial prowess, his life was marked by […]