The new world disorder, from rules to might

As the rules-based order erodes, raw power is beginning to reshape the global system A world that once imagined it had buried the demons of the 1930s now finds them prowling again — less dramatic, […]

As the rules-based order erodes, raw power is beginning to reshape the global system A world that once imagined it had buried the demons of the 1930s now finds them prowling again — less dramatic, […]

The use of force by the US in Venezuela raises doubts about the legitimacy of its actions “The fact that the US action flouts international law related to state sovereignty and humanitarian rights protocols has […]

WASHINGTON, D.C. (TIP): The United Nations says that beyond the social media announcement from the United States government on Jan. 7 about its withdrawal from 66 international and UN entities, the information has not been […]

Israel says the new regulation aims to prevent bodies it accuses of supporting terrorism from operating in the Palestinian territories UNITED NATIONS (TIP): UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres called on Friday, January 2, 2026, for […]

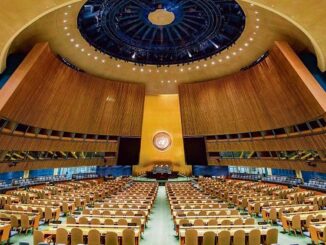

The 80th UNGA is in progress, and the eyes of the world are turned to the world body to see what the world leaders have in mind to work for peace, development and human rights. […]

The first step towards strengthening the multilateral system must, therefore, begin with removing the contradictions within the UN Charter on decision-making “As the UN prepares to mark its 80th anniversary in September 2025, it is […]

UNITED NATIONS (TIP): The United Nations Security Council on Thursday, October 3, 2024, expressed its full support for Secretary-General Antonio Guterres after Israel’s foreign minister said he was barring him from entering the country. The […]

The ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine, stretching back over a century, has been one of the most enduring and volatile disputes in modern history. In recent years, particularly with the leadership of Israeli Prime […]

DUBAI (TIP): The Taliban have suspended polio vaccination campaigns in Afghanistan, the U.N. said September 17. Afghanistan is one of two countries in which the spread of the potentially fatal, paralyzing disease has never been […]

UNITED NATIONS (TIP): Major Radhika Sen, a peacekeeper with the United Nations (UN) mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), has been honored for her outstanding efforts in empowering local communities, particularly women. “Receiving this […]

Though I was giving a positive message to readers of The Indian Panorama on January 1, 2024, we cannot ignore that over 30 live global conflicts are going on. Millions are displaced; International law is […]

Primary reason for the ongoing crises in Ukraine and Gaza is an ineffective Security Council The need to urgently reform the rules-based order has to be pursued through informal multiple-stakeholder consultations in the lead-up to […]

When will we learn that there are no victors in war. Ultimately, we are all losers. I pray that peace returns to the embattled war zone “Israel has weaponized its memories of the Holocaust so […]

“The ideals of Diwali are the ideals of UN Charter” : Chair of Diwali Foundation USA Ranju Batra UNITED NATIONS (TIP): Former UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon and three veteran diplomats were honored with the […]

Two months after Hamas attacked Israel, triggering a fierce retaliation, UN chief Antonio Guterres has invoked the rarely used Article 99 of the United Nations Charter to appeal to the Security Council to facilitate a […]

UNITED NATIONS (TIP): UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has used a rarely exercised power to warn the Security Council of an impending “humanitarian catastrophe” in Gaza and urged its members to demand an immediate humanitarian cease-fire. […]

Gaza (TIP): Israel pounded northern Gaza and said it was “extending” its ground operation late on October 27 amid UN warnings of an “avalanche of human suffering” in the battered Palestinian territory. “Following the series […]

MOSCOW (TIP): Heaping praise on India, Russian President Vladimir Putin has said that the Indian leadership is “self-directed” and led by the country’s national interests, according to Reuters. Speaking at an event, Putin alleged that […]

GENEVA (TIP): France must address deep issues of racial discrimination in its police, the United Nations said on June 30, after a third night of unrest sparked by the fatal police shooting of a teenager. […]

NEW YORK (TIP): Indian-Americans are preparing for a cultural extravaganza for Prime Minister Narendra Modi as he arrives in the American Capital from New York City after leading a yoga session at the UN Headquarters. […]

GUWAHATI (TIP): A conglomerate of 15 Manipur organizations has submitted a memorandum to the United Nations and international rights bodies seeking global attention to the ongoing crisis in the northeastern State. The organizations include the […]

UNITED NATIONS (TIP): Top United Nations officials voiced support for India’s initiative to establish a memorial wall honoring fallen UN peacekeepers as they lauded the country’s role and contribution to the global organization’s peacekeeping missions […]

WASHINGTON, D.C. (TIP): Indian American Republican presidential hopeful Nikki Haley has called for legal immigration based on merit, talent and business needs and would stop allowing any immigrants into the country before immigration reform. Legal […]

United Nations (TIP)- India is a “bright spot” in the world economy currently and is on a “strong footing”, projected to grow at 6.7 per cent next year, a very high growth rate relative to […]

Now more than ever, it is time to forge the pathways to cooperation in our fragmented world, he said DAVOS (TIP): The world is facing a perfect storm on multiple fronts and all that can […]

© The Indian Panorama