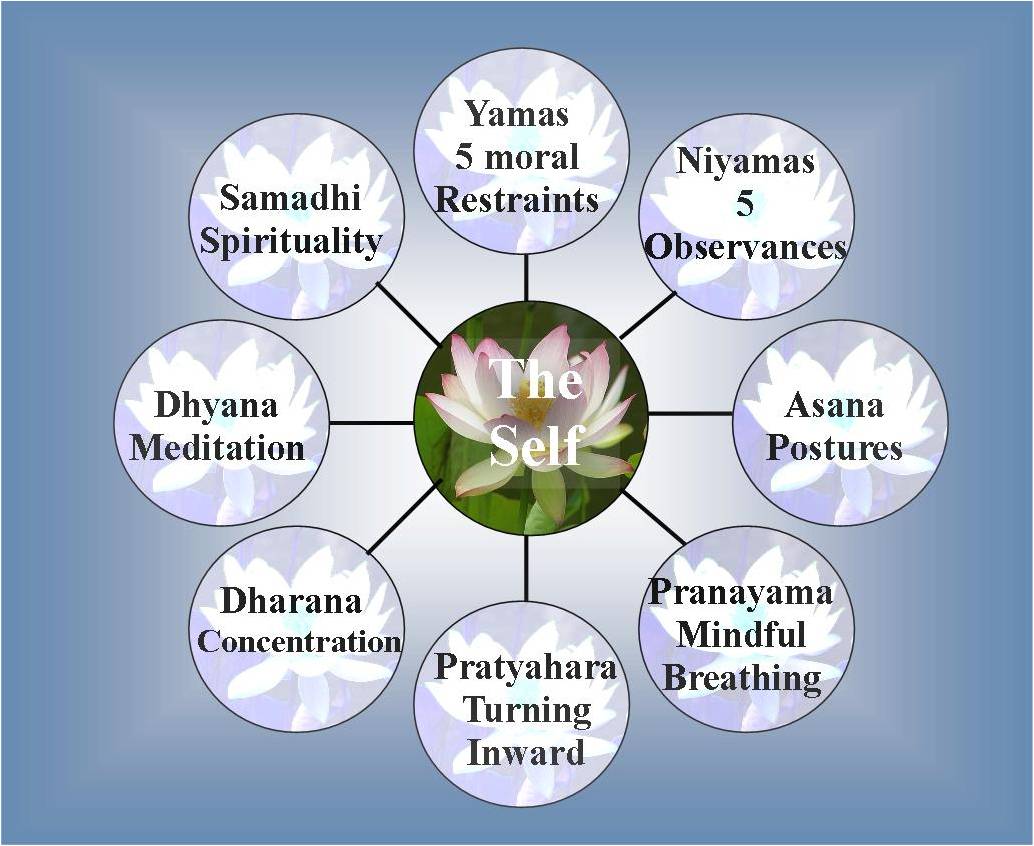

[quote_box_center]“It will be worthwhile putting asanas in the context of the complete discipline of yoga – Patanjali’s ashtanga yoga or eight-limbed system as expounded in only 196 pithy sutras in his treatise titled Yoga Darshan. The eight parts are: Yama, Niyama, Asana, Pranayama, Pratyhara, Dharana, Dhyan and Samadhi. Yama (like nonviolence and truthfulness) and Niyama (like purity and contentment) are don’ts and do’s which are commandments universal in nature and common with ethical practices of world religions”.[/quote_box_center]

The practice of yoga – even if it is only asanas or postures as is ubiquitous today – can serve as a window to the holistic and perennial philosophy of India. Frankly, the term ‘Indian philosophy’ is a misnomer. The Sanskrit equivalent is ‘Darshan’, which denotes seeing, witnessing, experiential learning. The font of Indian philosophy are, of course, the Vedas, which are considered ‘apaurashya’, meaning they are not what somebody wrote down, but a record of what our rishis (literally, seers) experienced in their consciousness. The truths and knowledge dawned in their consciousness after preparatory practices and tapas.

The practice of yoga – even if it is only asanas or postures as is ubiquitous today – can serve as a window to the holistic and perennial philosophy of India. Frankly, the term ‘Indian philosophy’ is a misnomer. The Sanskrit equivalent is ‘Darshan’, which denotes seeing, witnessing, experiential learning. The font of Indian philosophy are, of course, the Vedas, which are considered ‘apaurashya’, meaning they are not what somebody wrote down, but a record of what our rishis (literally, seers) experienced in their consciousness. The truths and knowledge dawned in their consciousness after preparatory practices and tapas.

Yoga is one of the six systems of Indian philosophy (Shat Darshan) that take their authority from the Vedas. These are Nyaya, Vaisheshik, Samkhya, Yoga, Purva Mimansa and Uttar Mimansa (Vedanta). There is enough play given to logic (as in Nyaya), or theoretical exposition of consciousness (as in Samkhya). But in time, Yoga and Vedanta have emerged as the cornerstone of Vedic religion, full flowering of the long-standing Indian tradition: Vedanta reaching the highest and noblest understanding of the ultimate reality as pure consciousness that underlies all creation animate and inanimate; and yoga offering practical and time-tested ways and means – asanas, pranayama and meditation – to experience that pure consciousness first hand. This is also considered the royal spiritual path- Raja Yoga.

True, most of us, caught up in our mundane lives and struggles, are not worried overmuch about esoteric subjects like the ultimate reality, or pure consciousness. Yet we all wish for health and happiness. That is where yoga appeals. Once you attend a yoga class, you notice right away how it goes beyond mere physical exercise. The structured set of asanas also relaxes the body and mind, creating equanimity. The health and other benefits of yoga are well-known (we will review them in another article in this series) and the reason the western world has cottoned on to this Indian import.

But, it will be worthwhile putting asanas in the context of the complete discipline of yoga – Patanjali’s ashtanga yoga or eight-limbed system as expounded in only 196 pithy sutras in his treatise titled Yoga Darshan. The eight parts are: Yama, Niyama, Asana, Pranayama, Pratyhara, Dharana, Dhyan and Samadhi. Yama (like nonviolence and truthfulness) and Niyama (like purity and contentment) are don’ts and do’s which are commandments universal in nature and common with ethical practices of world religions. They are suggested but not a pre-requisite to starting the practice of asanas and meditation. In fact, the system of yoga is as secular as you can get. You are not asked to worship any Hindu deity or sacred book, or have belief in God or a supreme power. Yoga can even claim to be scientific. As in any science experiment, if you practise yogic techniques properly and regularly, results are bound to accrue precisely like in H2+O making water. Asanas are physical postures. Pranayama is breathing practices. Pratyhara is withdrawal of the senses from sense objects. Dharana is concentration and cultivating inner perceptual awareness.

Besides devising the elaborate sets of asanas and breathing techniques, what tells Vedic religion and yoga apart from Occidental religions is in the enormous R&D in meditation or Dhyan, the seventh limb of yoga. Numerous practices, varying in complexity and degree of difficulty, have come down to us, thanks mainly to the guru-shishya parampara and the oral tradition. They are better learnt from a teacher; some are easily accessible like Transcendental Meditation or TM as taught by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi of the Beatles fame. Buddhism too digged deep into states of mind and developed meditation practices such as Vipassana as popularized by S.N. Goenka from Igatpuri in Maharashtra, and mindfulness, which has caught on lately in certain medical and corporate circles in America. Jains rediscovered Preksha Dhyan a couple of decades ago at the behest of Acharya Tulsi.

Samadhi is the meditative absorption attained by the practice of dhyāna. The mind becomes still. There are no thoughts; only consciousness, not of anything outside but of itself. That is why it is called pure or transcendental consciousness. Regular experience of this mystical state leads to it stabilizing outside the meditation sitting too. As Guru Nanak said in Japji sahib, ‘Naam khumari Nanka charhi rahe din raat’ – a permanent state of bliss and beatitude. Patanjali Yoga aims for Kaivalya or liberation. Buddhism targets Nirvana. Enlightenment and cosmic consciousness are terms used by others for the final fruit of a spiritual life.

So, let a thousand yoga studios and classes bloom. Nobody can take away from the fact that yoga originated in India. At the same time, no faith or system can claim a copyright over the mystical states which are potentially accessible to and a birthright of every human on this earth.

Be the first to comment